Memories

Related sites:

Life before August 1914

War starts

Life and Death

in Arborfield during the War

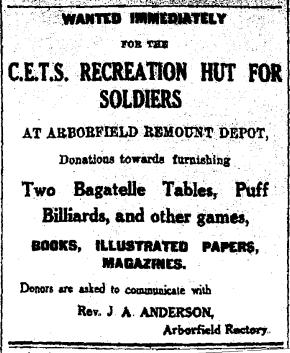

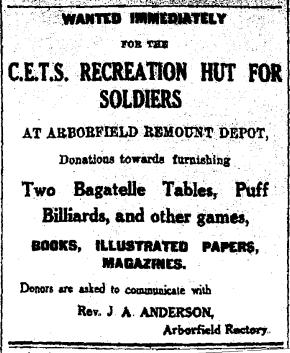

Arborfield Church and Rev. Joshua Anderson

Bearwood and the Canadian Convalescent

Hospital

The Remount Depot, Arborfield Cross

(actually, mostly in Barkham)

Life and Death

in Barkham during the War

Barkham Church and Rev. Peter Ditchfield

Fund-raising

Caring for the Refugees

Caring for the Wounded

From Volunteers

to Conscripts

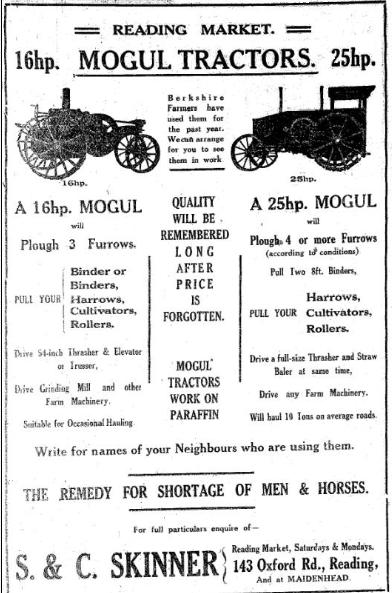

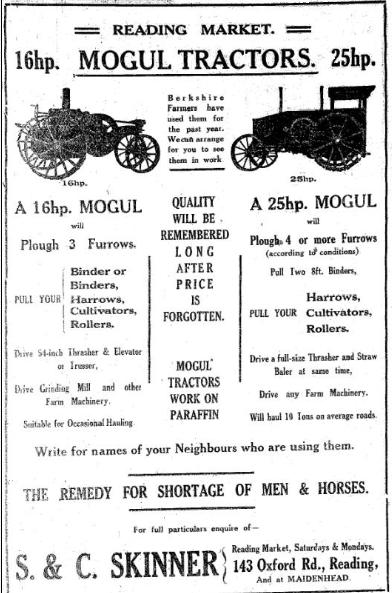

The Revolution in Agriculture

Zeppelin Scares

Food shortages and rationing

Prohibition or Moderation?

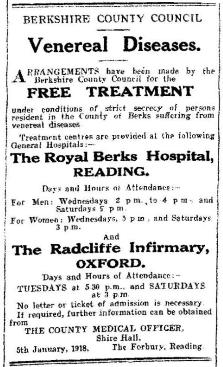

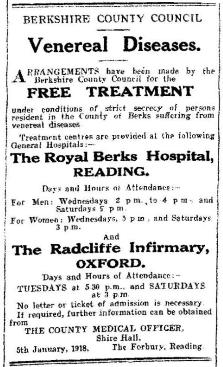

Health Matters

The Weather

Berkshire County

Council

Trivia

Armistice Day and after

Adjusting to

Peacetime, 1919 to 1922

|

|

The Reading

Mercury and Arborfield, 1914 – 1918

How was life in Arborfield portrayed

in the local newspaper in WW1?

This set of topics is composed mainly of quotations from articles

covering Arborfield and Newland, the Remount Depot, Barkham

and Bearwood (by the way, the mansion is almost entirely within the old

civil parish of

Newland).

Inevitably, many articles cover the wider area, especially

Reading and Wokingham, and are included where it is thought that they

would have been noted by Arborfield residents. Several residents, including John Simonds

of Newlands, worked in Reading (he was the Borough Treasurer as well as a

local director of Barclays Bank); we know of at least one apprentice who worked

in Reading, until he went to the Front and lost his life there.

The text in the articles is more or less as published, but the

paragraph layout has been altered to make it more readable. Many articles

appeared as a single large paragraph.

Images are taken from the Classified and other Ads. Either follow the links on the left, or in the following

summary, to navigate through

this feature.

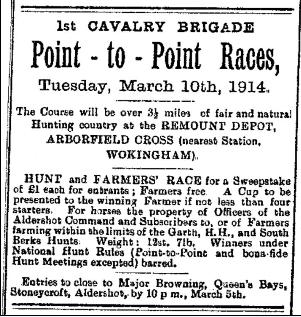

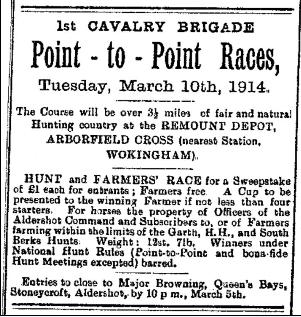

Arborfield and the Great War

Arborfield

in early 1914 was much as it had been in Edwardian

times .

Half the 200-odd population lived or worked for the big houses. The

Remount Depot

offered both local employment and some entertainment; every spring, hundreds of

people flocked to Point-to-Point Races where local farmers and gentry

competed alongside Army officers from Aldershot. .

Half the 200-odd population lived or worked for the big houses. The

Remount Depot

offered both local employment and some entertainment; every spring, hundreds of

people flocked to Point-to-Point Races where local farmers and gentry

competed alongside Army officers from Aldershot.

John Simonds of 'Newlands'

commuted into Reading where he both managed Barclays Bank and acted as Borough

Treasurer. Mrs. Hargreaves of Arborfield

Hall took great interest in village life, throwing summer parties in the

grounds beside the River Loddon.

Captain and Mrs. Rickman lived at the Grange,

Mrs. Bruce at the Court, and Mrs. Walter at

Bearwood Mansion. While Arborfield Hall had hydro-electric power and

Bearwood its own gas-works, most villagers relied on candles, and drew water

from the well.

The Rectors of Arborfield and Barkham,

Joshua Anderson and

Peter Ditchfield, were familiar

faces in Arborfield, both visiting the Village School regularly. Many of

the school teachers had served for decades;

Mrs. Allright had taught there since the 1880’s, while young

Miss Edwards had been a pupil there, and

moved on to teaching before she was able to attend college. The school Summer

Party in July 1914 took place as usual in the grounds of

Arborfield Hall.

Other villages in Berkshire weren’t quite so lucky; summer events that

normally took place in August were abruptly cancelled as

war was declared. Men

immediately volunteered for the Front, while the civilians at the Remount

Depot became soldiers overnight, and there was a recruiting drive for

farriers and grooms in the local papers.

The local paper was the ‘Reading Mercury’, which carried reports from all

of the villages in and around Berkshire, including Arborfield and Barkham. It

was old-fashioned, with classified adverts on its front pages, and in 1914 it

never printed any photographs. Its rival the ‘Reading Standard’ was

always full of photos, and in Spring 1914, it had profusely illustrated features

on the new life to be found in Canada.

Later, the 'Standard' would encourage volunteers to serve by publishing photos

of the young men from ‘patriotic families’, such as the Clacey boys from

Finchampstead. Both newspapers reported on national and international affairs,

and increasingly on ‘our Boys at the Front’. As the War went on, they issued

lists of the wounded and killed, and reported on the wounded Canadian and other

soldiers being treated in Berkshire.

The local towns played host to hundreds of refugees from Belgium and France,

most of whom stayed for the duration of the conflict.

As the months extended into years, Reading became the focus for treating the

wounded – the old Workhouse was transformed into Battle Hospital. The

Reading V.A.D. group could transfer a whole train-load of walking-wounded and stretcher-cases to the

hospitals within an hour.

could transfer a whole train-load of walking-wounded and stretcher-cases to the

hospitals within an hour.

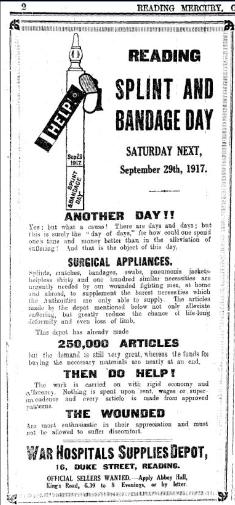

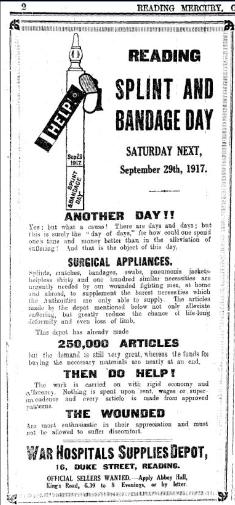

The town held ‘Splint and Bandage’

days, and the surrounding villages collected Sphagnum Moss to

make absorbent dressings.

There were collections to fund the ‘Berkshire

Room’ at the new ‘Star and Garter Home’ in Richmond, acquired by the

Auctioneers’ and Estate Agents’ Institute for the nation.

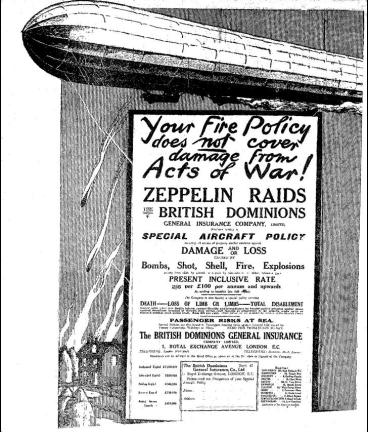

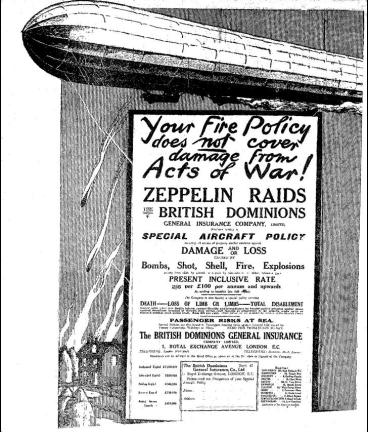

By 1915, London and some provincial cities were

being bombed by Zeppelin airships, and

insurance

companies

spotted a gap in the market. Large adverts appeared in the ‘Mercury’, pointing

out that normal house insurance didn’t cover enemy attack. companies

spotted a gap in the market. Large adverts appeared in the ‘Mercury’, pointing

out that normal house insurance didn’t cover enemy attack.

On the night of 6th March, Reading was on

full alert, but the Zeppelins headed elsewhere and the town was spared.

Both the towns and the countryside had to be partially blacked-out, just in case

of attack. However, this caused more casualties than enemy bombing.

Ralph Pomeroy Simonds, who grew up

in Farley Hill and farmed in Surrey, was killed in the dark when he skidded on

his motorcycle trying to avoid a pedestrian. His funeral took place at

Arborfield Church.

Bearwood Mansion was taken up by the Army in late 1914 and assessed for

its suitability as a hospital. It played host to thousands of wounded soldiers

in its role as

the Canadian Convalescent Hospital.

At one point 900 wounded soldiers were there, some almost fit enough to return

to the Front. Certainly, several were fit enough to form a formidable football

team, aided by the Vicar of Bearwood (and also the hospital Chaplain) Major

Bayley, who scored over 100 goals for them in the 1917-18 season. The team

also had a Nottingham Forest footballer from the hospital staff. In addition,

they played baseball at Elm Park, home of Reading Football Club. the Canadian Convalescent Hospital.

At one point 900 wounded soldiers were there, some almost fit enough to return

to the Front. Certainly, several were fit enough to form a formidable football

team, aided by the Vicar of Bearwood (and also the hospital Chaplain) Major

Bayley, who scored over 100 goals for them in the 1917-18 season. The team

also had a Nottingham Forest footballer from the hospital staff. In addition,

they played baseball at Elm Park, home of Reading Football Club.

The Canadian soldiers, both staff and patients,

frequented the village pubs in Arborfield. In 1916

Mrs. Clark, landlady of the

‘Swan’, was summoned to appear in court for

serving Canadian wounded soldiers with alcohol, which was strictly

against the law. P.C. Prior had arrested three Canadians, one so drunk

that he was temporarily legless and had to be taken back by ambulance. The case

was thrown out because the patients had unstitched the armlets that identified

them as wounded, and so the pub staff weren’t to know.

Meanwhile, Trooper Alfred Duffield, on

the staff of Bearwood Hospital, had been courting

May Bushell, daughter of the Landlord

of the ‘Bull’. They married at Arborfield Church in June 1917.

The same month, Dolly Powell, from

the Lodge at Arborfield Hall, married Ernest Finch at Arborfield. Mrs.

Hargreaves gave presents to both couples, and even hosted the reception at the

Reading Room in Church Lane for Dolly and her husband. May Bushell’s wedding

reception couldn’t fit into the ‘Bull’, so they used a marquee on the Garrett

Brothers’ meadow opposite.

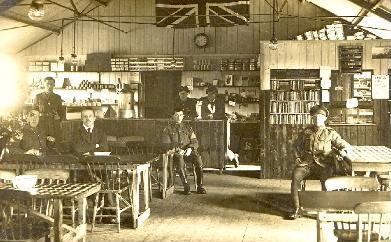

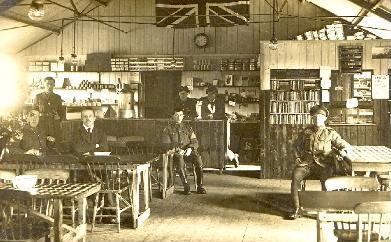

The Church had long been concerned about the

effect of alcohol on soldiers. The

Y.M.C.A.

provided a recreation hut at Bearwood and laid on entertainment, as an

alternative to the attractio Y.M.C.A.

provided a recreation hut at Bearwood and laid on entertainment, as an

alternative to the attractio ns

of local public houses, while the Church of

England Temperance Society erected a similar hut at the Remount Depot,

opened by Mrs. Stuart Rickman, who had come down from her London house for the

occasion. ns

of local public houses, while the Church of

England Temperance Society erected a similar hut at the Remount Depot,

opened by Mrs. Stuart Rickman, who had come down from her London house for the

occasion.

By late 1917, there was talk of possible

Prohibition, with packed meetings in Reading Town Hall to hear speakers

from Canada, which was to be ‘dry’ for the duration of the war, and the USA,

where 27 States had already imposed Prohibition, destined to last well

into the 1920’s. England escaped with stricter licensing laws, weaker beer and

earlier closing times.

The villagers did their bit to grow more fruit

and vegetables, but unlike some of its neighbours, no areas were provided for

Allotments. Also unlike Swallowfield, Barkham and the Remount Depot, the village

didn’t run a ‘Rat and Sparrow Club’, which paid a bounty for each one

killed; rats and sparrows were seen to compete for grain.

Food became very scarce in Reading partly due to the large number of

wounded and

refugees, and by January 1918 there was so little meat that the butchers had to

close on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

Food rationing was introduced amid scenes of near-riots in West Street,

which only calmed down when the Mayor commandeered a tram from which to address

the crowds.

From at least 1916, the Remount Depot held summer

Sports Days where all the

villagers were welcome to attend and compete. Some of the soldiers had an

advantage; the prize for kicking the football for the furthest distance was won

by Sergeant Steer, in peacetime a Chelsea international player. By

1917 the Sports Days included fruit and

vegetable competitions to encourage gardening, and in

1918 there were Rabbit and Goat

Shows, again to encourage villagers, this time to keep livestock.

Bearwood also held Sports Days,

including swimming races in the lake.

Agriculture had to change because of

the shortage of labour. Women started working on the farms, and local firms

started selling tractors, allowing farmers to save on scarce labour.

The Army

offered soldiers from the Reading barracks as temporary agricultural workers.

It was all change in the big houses, too:

Mrs.

Walter died at Bearwood;

Mrs.

Hargreaves died at Arborfield Hall.

Mrs. Bruce sold Arborfield

Court, while

Mrs. Stuart Rickman sold

Arborfield Grange.

Arborfield Hall was put up for

auction in 1919, as was Carter’s Hill Farm.

Some of the Farm was sold on to Berkshire County Council to form

smallholdings for returning soldiers. There were

two at Betty Grove Lane.

A notice about ‘eggs for wounded soldiers and sailors’ appeared

weekly for most of the war and into 1919. The scheme was based at Hartley Court, home of Mrs. Max de Bathe, in Three Mile Cross, and it hosted

several fund-raising events. Other country houses also assisted the war effort,

producing 'Anti-Vermin Garments'

for the troops at the front.

This advert in January 1918 would have caused shock-waves. It announced that

people could attend free clinics for Venereal Diseases at the Royal Berks

Hospital. The advert was followed in Spring 1919 by several

similar notices as the soldiers were de-mobbed. This advert in January 1918 would have caused shock-waves. It announced that

people could attend free clinics for Venereal Diseases at the Royal Berks

Hospital. The advert was followed in Spring 1919 by several

similar notices as the soldiers were de-mobbed.

Reading was hit by ‘Spanish Flu’ in late October 1918, and again in February

1919. On March 1st 1919, the ‘Mercury’ reported 23 deaths in the previous week

from influenza and pneumonia.

A series of 13 adverts for National War Savings in late Summer 1918 would have

caused no controversy at all. Its symbol was a swastika – but this didn’t

acquire a sinister meaning until the Nazis hi-jacked it 15 years later.

Armistice Day on November 1918 was the cause for thanksgiving and celebration.

Church bells and factory hooters made a tremendous noise. The following Friday

there was a torchlight procession from the Remount Depot to Arborfield Cross,

where there were fireworks, a bonfire and a mock trial of ex-Kaiser Bill and the

ex-Crown Prince. Adjustment to peacetime

conditions took far longer.

Early in 1920 Mrs. Rickman came out from London for the unveiling of the new

War

Memorial at the Cross, helped by John Simonds & Rev. Anderson.

Back to Memories Page

|

The 'Reading Mercury' and the 'Berkshire

Chronicle' were very conservative in their formats. The 'Mercury'

consisted of 12 pages, which shrank to 8 during the early war years because of

paper shortages. There were line drawings, but no photographs until very late in

the war.

There was another more populist newspaper,

the 'Reading Standard', which in contrast was filled with photographs

both before and during the War, and especially featured cameo pictures of soldiers volunteering,

mentioned in dispatches, wounded or killed.

The 'Reading Standard' produced a hard-back

commemorative series after the War, which can be seen at the Reading

Local Studies Library, and is now available in CD form from the

Berkshire Family History Society.

|