September

|

Arborfield

|

|

Memories

Related sites:

"Byways in Berkshire and the Cotswolds", by Peter Ditchfield, 1920

Full text of Notes on the Old St. Bartholomew's Church for a talk given by Peter Ditchfield |

Chapter 8 of "Byways in Berkshire and the Cotswolds", part 1, by Rev. Peter Ditchfield, describes a journey through Arborfield. The journey from Wokingham through Peter Ditchfield's parish of Barkham would have been much different than now. Before 1920, about the only buildings between the "Leathern Bottle" and Barkham Hill would have been the thatched cottage on the bend in the road, and Doles Farm. The ribbon development which characterises Barkham Road, Bearwood Road, Langley Common Road and School Road took place from the 1920s onwards.

VIII - Wokingham to Miss Mitford's Country CROSSING the railway at Wokingham station we pass along the Barkham Road. Journeying about a mile we come to the "Leather Bottle Inn" which, although it had been entirely rebuilt, Prince Christian always imagined appeared in one of Morland's pictures. He once asked me to investigate the matter, and I spent some time in the British Museum endeavouring to discover the truth of the claim. I found that the painter was certainly in this neighbourhood when he stayed at inns, painted pictures and sold them to defray the cost of a night's lodging and a drunken carouse; but nothing certain could I find. Old names linger long in our country. We pass on the left Dole's Farm. In Norden's map, made three hundred years ago, Dole's Hill is recorded. So we pass to my village of Barkham where these lines are written, and the story of which I have told in some of my books.

It is a very pretty village and its history is ancient, dating back to the time when a Saxon thane gave Bloreham to the monks of Abingdon Abbey in 951 a.d. Its boundaries are given in the chronicle. In Saxon times it passed away from the rule of the abbey and in the time of King Edward the Confessor it was in the possession of a Saxon thane named Aelmer. After the Conquest it was taken possession of by William the Conqueror who doubtless often hunted the "tall stag" within its boundary. I have traced the history of the descent of the manor in the Victoria County History of Berkshire. The most notable of its owners were Sir Thomas Neville whose daughter Agnes (sometimes styled Anne de Neville) brought by marriage the manor to Gilbert Bullock of Arborfield, whose family held it until the end of the sixteenth century. We may scent a little romance in this marriage. Gilbert's father, Robert Bullock, had been trustee for the Crown of certain land in Barkham supposed to belong to John Mautravers, and forfeited by him to the king on account of his treason. To this land Agnes made a successful claim, on the ground that she had been wrongfully dispossessed of it by Mautravers, and Robert Bullock was authorized to make it over to her in 1335. Then finding Mistress Agnes a considerable heiress he arranged a marriage between her and his son Gilbert. The Bullocks sold the manor with that of Arborfield to Edward Standen in whose family it remained for some time. At the end of the eighteenth century the manor was purchased by Lady Gower and was held by the Hon. Admiral Leveson Gower and his descendants, until it was bought by Mr. John Walter whose grandson is now the lord of the manor, although the manor house has been purchased by Mr. A. N. Garland. In the Public Record Office there is a very early document relating to the village, the king's reeve's account of the manor temp. Edward I. It is the only one of that early period extant, and records the sale of the produce of the manor, including "iis. id. for the yield of x cocks and x hens." There was an old church dedicated to St. James in the village, but unhappily the Goths and Vandals of the nineteenth century pulled it down in 1860 and erected a brand new church which has many merits. The chipped flint work of its walls is admirable, and it has a graceful shingle spire. Mr John Walter, who has left his mark upon so many villages in the district, added a new chancel and transepts, and built a new rectory, I have recovered the ancient door of the church which reposed for many years in a garden in Wokingham. There is a much battered wooden effigy of a lady in the porch, believed to be that of Mistress Agnes Neville, the daughter of a lord of the manor in the fourteenth century, whose acquaintance we have already made and who married the son of Robert Bullock, squire of Arborfield, and thus united the two manors which remained in the Bullock family for many years. We have an ancient and beautiful Elizabethan chalice, the date letter recording that it was fashioned in 1561, a paten of 1664 given by John Stronghill "when he was heade-churchwarden"; another paten given by one of my learned predecessors, Dr. Gabriel, and a noble flagon, the gift of Dame Rebecca Kingsmill in 1729. These treasures we prize very highly. The present manor house does not date back earlier than the last century. I remember the village pound which disappeared about thirty years ago, and a curious stand for shoeing oxen that formerly stood near the smithy of the "Bull Inn". In this hostel the old Court Leet and Court Baron were held, and the tithe dinners which must have been days of trial for the rector and of revel for the tithe payers. Some paid a small tithe of a few shillings and always determined to make up for this payment by eating and drinking as much as possible. Before the war the inn used to provide suppers for the ringers and for the cricket club, and to resound with decorous merriment on their festal occasions. One of the most remarkable of my predecessors was the Rev. Dr. David Davis who held the living from 1782 to 1819. He also acted as chaplain to Lady Gower of Bill Hill who owned the manor, and I have in my possession a note book of his in which he recorded his receipts and expenditure. Some of the items are curious. He was chaplain to Lord Cremorne and received £10 a year for his services. Lady Cremorne paid the expenses of a curate when he attended the family in France, but he protested that he had no right to the money. He farmed and sold the produce to the farmers and gentry in the neighbourhood, and was much troubled about some money that was owing to him in Barbadoes, and was doubtful whether he would ever receive it. He was charitable, paid for children's schooling, gave money to shipwrecked tramps ("impostors"), lost money at cards, paid £2 3s. for a bob wig block and stand. The book is amazingly interesting, and I hope to describe its contents more fully some day. But his chief title to fame and to the affectionate regard of his own and of future generations is that he made a careful examination of the economic condition of the labouring poor. He was the author of The Case of Labourers in Husbandry, published in 1795, and this book together with Eden's State of the Poor, published two years later, is the chief authority on social conditions in the eighteenth century. My worthy predecessor is less famous than he deserves to be if we are to judge from the fact that the Dictionary of National Biography only knows about him that he was rector of Barkham in Berkshire, and a graduate of Jesus College, Oxford, that he received a D.D. degree in 1800, that he is the author of this book, and that he died, "perhaps, in 1809", which he certainly did not. But Davis's book which contains the result of most careful and patient investigation, made a profound impression on contemporary observers. Hewlett called it "incomparable", and it is impossible for the modern reader to resist its atmosphere of reality and truth. This country parson gives us a simple, faithful and sincere picture of the facts, seen without illusion or prejudice, and free from all the conventional affectations of the time: a priceless legacy to those who are impatient of the generalisations with which the rich dismiss the poor. He gives tables of the actual receipts of labourers' families in Barkham and in other parts of England, and of the actual necessary expenditure, and shows how impossible it was in those days for them to live and bring up their families. Some day I hope to collect the details of his life, and can only now just mention his conclusions. He wrote: "Allow the cottager a little land

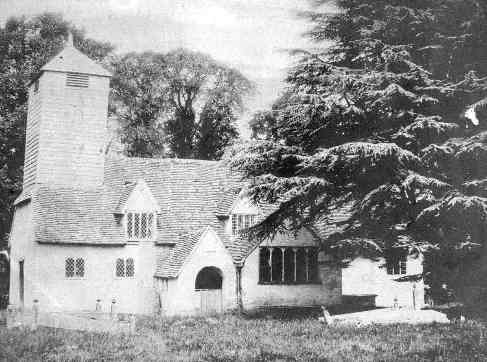

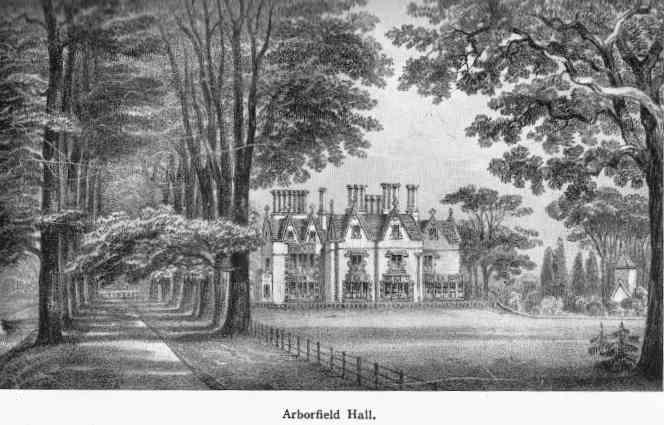

about his dwelling for keeping a cow, Our registers date back to 1538, the first year that Thomas Cromwell ordered such books to be kept, showing that even then the rectors of Barkham were good and obedient men and readily conformed to the orders imposed upon them, a character which I hope they have not since lost. In "the short and simple annals of the poor," and of the squires and farmers there is much of interest. The first recorded name is that of Ball which family was very prolific, and I have tried to prove that they were the ancestors of Mary Ball, [Out of the Ivory Palaces. by P. H. Ditchfield.] who was the mother of President Washington. Americans have sometimes come to search this old book to find traces of their ancestors, and I shall not forget the delight of some of those searchers who have discovered that for which they sought. There were two moated farmhouses in the parish that testify to the wild nature of the Forest in olden days when it was found necessary to have some such protection from outlaws and roving bands of gipsies. Barkham was also rather famous for a family of parish clerks. A story I have told elsewhere of Elijah Hutt is worth retelling. When the new church was being built Elijah found his way with some companions to the neighbouring church of Finchampstead one Sunday. He arrived just as the first Lesson was being read, and during its course the clergyman called out in stentorian tones, "What doest thou here, Elijah?" Elijah was rather startled, but remained silent. However when the query was again repeated with emphasis, he imagined that it must be addressed to him. So he arose in his place, touched his forelock, and replied, "Please, sir, Barkham church is undergoing repair, so we be cumed here." Another story is told about his son who was a great character. Sometimes he used to fall asleep during the sermon, and on one occasion when he was expected to say a decorous "Amen", he called aloud "Fill 'em up again, Mrs. Collyer, fill 'em again." Now, Mrs. Collyer was the much respected landlady of the "Bull Inn", and the conclusion is obvious. During many years right into my time he served the parish well in his old-fashioned ways, and I missed him more than I can say when he died. The war has made us a semi-military village and khaki is seen everywhere. We have a Remount Depot just beyond our borders. Horses and mules parade our roads and dwell in our fields, and we send them with sad hearts on their way to the front to help our men to fight our battles for England and to win the victory. But I must not keep you too long in this pleasant village. We must pass on to Arborfield Cross, or Arofield Cross, as it appears in Norden's map. I may say a word or two about the derivation of the name, showing that even learned men may err. The unlearned etymologist at once declares that of course Arbor is the Latin for a tree, and field is, of course, a field, in place where trees were felled. But that is a strange hybrid sort of name, a mixture of Saxon and Latin of which every one who knows anything of the science of language would naturally beware. Yet mirabile dictu Professor Skeat fell into error over this name. He says it is comparatively modern, and connects it with the Anglo-French herber or erber, a herb-garden or arbour. In order to discover the correct derivation of a word it is necessary to find out the original mode of spelling it, and Arborfield appears in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as Edburgefeld and Erberge feld and Hereburgefeld, and signifies the field or settlement of a man named Hereburgh. The Cross has a picturesque, old, half-timbered house, the post office, with a smithy adjoining it, a pretty green, and an old inn called the "Bull". Here five roads meet, the road we have traversed from Barkham continuing to Shinfield and Reading. That to the right conducts you to Bearwood and Wokingham, and on the left are two roads, one leading to Eversley and Aldershot, and the other to Swallowfield. Unexpected discoveries are made sometimes of the prehistoric folk who inhabited our fields and villages. Some men employed in the building of Arborfield Court brought to me some old pottery taken from a spot eight or ten feet below the surface of the ground on a hill, that was evidently a prehistoric burial mound or tumulus, and in a field in the parish a Celtic gold coin was found recently. These facts have been hitherto unpublished. But the chief interest of the place is associated with the hall and manor. I have often had occasion to mention the Bullock family. They were important people and of great antiquity. (The various branches of the family have been admirably recorded by Mr. Llewellyn Bullock, a Rugby master, in a privately printed volume.) Osmund Bulloc of Arborfield in 1190 presented my predecessor John, Rector of Barkham, to the charge of the chapel there. He was not very careful in the selection of his curates. One of these bright clerics in an archidiaconal examination failed to parse the sentence " Te, pater clementissime, oramus," and when asked what goverened "Te," replied, "Pater, because the Father governed all things." These Bullocks served well their generations, indeed, almost countless generations, their tenure lasting until the end of the sixteenth century. The support of large families and accumulated debts necessitated the sale of the property, which was purchased by Edmund Standen of Chancery, father of Sir William Standen, whose family held it for 150 years. The beautiful Jacobean Manor House, the ruins of which we shall presently hear Miss Mitford describing, was built by them. John Thorpe was the architect. It had a large entrance hall, so great that it was said a carriage could drive through it. When Edward Standen, the last of his race, the victim of Molly Mogg's attractions (to whom I have referred), died in 1730, the estate was bequeathed to his wife; and then after her death it devolved upon his heir Richard Aldworth, the ancestor of Lord Braybroke, then a minor, and was sold by his guardian under an Act of Parliament (4 Geo. II) to Pelsant Reeves, whose son John had two children, Pelsant and Elmira. Pelsant was Captain of the 1st Royals and was killed at Toulon in 1793. His fellow-officer and friend George Dawson, a Yorkshire squire, of Osgodby Hall, used to visit at Arborfield; and a friendship resulted in George Dawson marrying the heiress Elmira, who had a fortune of £10,000 and the estate. (History of the Dawson Family. By P. H. Ditchfield, privately printed.) These Dawsons are of royal descent, and can trace their pedigree to King Edward III, through his son Lionel, Duke of Clarence. Their history is extraordinarily interesting, and this I have traced by the aid of family papers, but it would be too long to be told here. Sometimes they were even extremely prosperous; then poverty stood at their gates and demanded entrance. In spite of the increase in fortune brought to George Dawson by his marriage, and owing to a vast expenditure and the maintenance of Osgodby Hall and Arborfield Hall, financial troubles befell the family. The old Berkshire house was in bad repair. Much money was needed to restore it, and this was not forthcoming. "Pull it down," said the owner in a hasty moment speaking at random. The order was eagerly seized upon by the steward of the manor and at once executed. Axes and hammers were turned upon the famous mansion, and doubtless the steward largely benefited by the outrageous destruction. So "the old house at Aberleigh" perished. When George Pelsant Dawson, son of George Dawson, inherited the property, he determined to rebuild the hall as much as possible, residing at the cottage while the work was in progress. He sold the property to Sir John Conroy, keeper of the Priory Purse to the Duchess of Kent, the mother of Queen Victoria, who built a portion of the present house. For some reason he incurred the displeasure of the young Princess, and one of her first acts on coming to the throne was to banish Sir John from the Court. He retired to Arborfield. The house was much enlarged by Mr. and Mrs. Hargreaves, who bought the place, while the old courtier retired to the cottage which has taken to itself wings and blossomed out into Arborfield Grange. Miss Mitford has left us a description of the elder house and this I cannot refrain from quoting: "And crossing the stile we were immediately in what had been a spacious park, and still retained something of the character, though the park itself had long been broken into arable fields and in full view of the Great House, a beautiful structure of James the First's time, whose glassless windows and dilapidated doors form a melancholy contrast with the strength and entireness of the rich and massive front. The story of that ruin for such it is is always to me singularly affecting. It is that of the decay of an ancient and distinguished family, gradually reduced from the highest wealth and station to actual poverty. The house and park, and a small estate around it, were entailed on a distant relative and could not be alienated ; and the late owner, the last of his name and lineage, after long struggling with debt and difficulty, farming his own lands, and clinging to his magnificent home with a love of place almost as tenacious as that of the younger Foscari, was at last forced to abandon it, retired to a paltry lodging in a paltry town, and died there about twenty years ago, broken-hearted. His successor, bound by no ties of association to the spot, and rightly judging the residence to be much too large for the diminished estate, immediately sold the superb fixtures, and would have entirely taken down the house, if, on making the attempt, the masonry had not been found so solid that the materials were not worth the labour. A great part, however, of one side is laid open, and the splendid chambers, with their carving and gilding, are exposed to the wind and rain sad memorials of past grandeur. The grounds have been left in merciful neglect; the park, indeed, is broken up, the lawn is mown twice a year like a common hay-field, the grotto mouldering into ruin, and the fishponds choked with rushes and aquatic plants; but the shrubs and flowering trees are undestroyed, and have grown into a magnificence of size and wildness of beauty, such as we may imagine them to attain in their native forests. Nothing can exceed their luxuriance, especially in the spring, when the lilac, the laburnum, and double-cherry put forth their glorious blossoms. There is a sweet sadness in the sight of such floweriness amidst such desolation; it seems the triumph of nature over the destructive power of man." (It may be observed that Miss Mitford was not quite correct in her statement about the Dawson family. Mr. Vincent in Highways and Byways in Berkshire is hopelessly wrong, as I have already pointed out (cf. p. 48).) Part of the old house is preserved in the stables of the present mansion, and a very fine bit of mellow brickwork it is. It is interesting to note that when Mr. and Mrs. Hargreaves purchased the estate they were ignorant concerning the Dawson ownership, and Mrs. Hargreaves, who is a descendant of the American branch of that family, was especially charmed to find herself in the home of her ancestors. Close to the old house stands the ruins of the old church of St. Bartholomew. About half a century ago the timbers of the roof were deemed to be unsafe. The church was a long way from the village and very close to the Hall; so Sir Thomas Browne, a relative of Mrs. Hargreaves, generously built a very handsome new church more easy of access to the villages, and the old church was left to moulder and decay. Embowered in a thick, interlaced bower of yew, holly, pine, honeysuckle and tangled growth, the remains of this little thirteenth century church present a scene of crumbling melancholy beauty that is pathetic. The east end wall clad with ivy still stands. On the splays, when wind and rain had worked their will upon them, some interesting mural paintings were disclosed. We walk along the central aisle of the old nave formed of large red tiles uneven and worn. Beneath our feet are tombstones scarred and scratched. We ascend the three brick steps leading to where the altar stood. There is a piscina, and on the floor two small tablets to the Hodgkinsons rectors of Arborfield, and of the wife of one of them who died in the second year of her marriage: "A sigh the absent claims, the dead a tear; Another inscription records : Heere lyeth the body of Thomas Haward, Gent, wth Anne his wife & Frances there onely child who was married to William Thorold Esq. and has issue 7 sones & 7 daughters. This Thomas Haward depted T 24th of November ao dmi 1643. When the old church was dismantled, the north aisle was restored and re-roofed and divided into two portions. There is a porch leading to the southern division, and the old door of the church with a beam over it bearing the date 1631. Around the walls are many marble tablets to the memory of the Conroy family who were of Irish origin, and are now, I believe, extinct. In the other portion are the memorials of the Standens, including a fine alabaster tomb of Sir William Standen (1639). Another Grey's Elegy might be written upon the dismal graveyard, and with mournful feelings the pilgrim passes into the park and resumes his walk. At the gate of the park there is a delightful cottage, L-shaped in plan, with a tall gable and tile-clad roof and well-tended garden. I have often wished to restore this charming little example of humble domestic architecture. Crossing the Loddon by a new bridge we think of Pope's line "The Loddon slow with verdant alders crowned", and find ourselves in the parish of Shinfield. Lord Ribbesdale, when he was Master of the Royal Buck Hounds, trusting in the information of a lady that there was a ford here, plunged gallantly into the flowing tide and was nearly engulfed. The inn on the left bears the sign "Magpie and Parrot", presumably alluding to the effect of good liquor in making its votaries talkative. School Green has a fine old set of school buildings founded by Richard Pigot in 1707, and endowed by him. So we pass to the church wherein doubtless Miss Mitford worshipped, as Three Mile Cross, the original of Our Village, is in this parish. It stands on a hill, whence a fine view is seen over a vast tract of hill and dale. In the valley below, the gentle Lodden [sic] winds on in bright and tranquil loveliness; a little further and just peeping from its sylvan covert are the gables of Arborfield Hall, and in the distance may be seen curling above the summit of thick woods by which it is screened, the blue smoke of "Our Village." The manor house adjoins the churchyard, formerly the old rectory, the seat of the Cobhams. An embryo "Garden City" with modern red-brick cottages dotted down as if from a monster pepper-caster, does not improve the appearance of the village. The church is interesting, mainly Decorated and Perpendicular with a fine seventeenth century brick tower. In the church there are some interesting monuments, notably one to the Beke family of Hartley Court, representing the husband and his wife Jane and his daughter Eliza kneeling at a prayer desk. There is another to the Martyn family (1607) and Edward Martyn in 1596 built the chapel at the east end of the south aisle. So we pass by a pleasant road past the modern vicarage to that little nest of houses where the immortal book was born, and where the gentle soul of Mary Russell Mitford lived in the early years of her literary life. She was one of the earliest of lovers of country life, who first unfolded the pages of Nature's book. To her shrine we make our pilgrimage, and try to see those same sights her kindly eyes beheld and her pen so sweetly and lovingly described. Dearly did she love her Berkshire home, the village she made so famous. "No prettier country could be found anywhere", she once said, "than the shady, yet sunny Berkshire, where the scenery, without rising into grandeur, or breaking into wildness, is so peaceful, so cheerful, so varied, and yet so thoroughly English". Nor was it only the trees and flowers that delighted her gentle spirit. She had a great love of humanity, a keen insight into the romance of rustic life. How graphically and with what affectionate interest does she describe her homely neighbours, and how fondly does she dwell on some little love story in the lives of her village youths and maidens. We can picture her neighbours as vividly as though we were living amongst them nigh a century ago. There is the retired publican, a substantial person with a comely wife, one who piques himself on independence and idleness, talks politics, reads newspapers, hates the minister, and cries out for reform. There is the village shoemaker, a pale, sickly-looking, black-haired man, the very model of sober industry; the thriving and portly landlord of "The Rose", Miss Phoebe, the belle of the village, and a host of others who live again in the pages of Our Village. She had a kindly interest for them all and wove romances about them, and could be very angry if her plans fell through and she discovered that "the best laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley". I remember the wife of John W telling me how vexed Miss Mitford was because John, who used to look after her garden, would not marry her maid, and preferred my informant, the present Mrs. W. Three-Mile-Cross is three good miles from Reading, and three from Swallowfield, the home of the Russells, the story of which the present Lady Russell has so beautifully told. The little Berkshire hamlet known throughout the world as "Our Village", is a long, "straggling, winding street at the bottom of an eminence, with a road through it, always abounding in carts, horsemen, and carriages, and lately enlivened by a stage-coach from B to S, which passed through about ten days ago, and I suppose will return some time or other". It is not a very magnificent village; there is no venerable church, no village green. There is an inn with its signpost, and about a dozen cottages, built of brick, a shop or two, and wheelwright's sheds. That is all! The house itself, where Miss Mitford lived for thirty years, is now a temperance tavern, and at the back of the house, in the garden which she loved so well, once boasting of "its pinks and stocks and carnations, and its arbour of privet not unlike a sentry-box", stands a temperance hall, fitted up with the usual unsightly accessories. Miss Mitford tells us what her home looked like in her time. "A cottage no, a miniature house, with many additions, little odds and ends of places, pantries, and what not; all angles, and of a charming in-and-outness; a little bricked court before one half, and a little flower-yard before the other; the walls, old and weatherstained, covered with hollyhocks, roses, honeysuckles, and a great apricot tree; the casements full of geraniums (Ah! there is our superb white cat peeping out from among them); the closets (our landlord has the assurance to call them rooms) full of contrivances and corner cupboards; and the little garden behind full of common flowers, tulips, pinks, larkspurs, paeonies, stocks, and carnations, with an arbour of privet where one lives in a delicious green light, and looks out on the gayest of all gay flower-beds". Its present appearance can only be described as disappointing. One would like to see at least one room kept as Miss Mitford kept it, packed round with books up to the ceiling, with some relics of the authoress which might be gathered together, with some portraits of her friends, Mrs. Trollope, Lady Russell, Mrs. Hofland, Miss Strickland, Mrs. Opie, Harriet Martineau, and Mrs. Jamieson, and sketches of the country she loved so well. A Mitford museum would indeed be a delightful addition to this poor modern temperance tavern. Here her parents died, and are buried at Shinfield Church, about a mile away, the ancient tower of which rises above the trees in the distance. We need not follow the fortunes of her father, the poor thriftless doctor, who won £20,000 in a lottery, gambled and lived extravagantly, and brought himself and his family to poverty. He had lived in great style at Bertram House, Grazeley, about one mile from " Our Village", but the house has been pulled down. There is, however, a delightful grassy road lined with tall elms, which we must see. Miss Mitford's favourite haunt; and as I ride along it I sometimes seem to see her graceful figure seated on some fallen trunk, writing with her paper spread on her knee, playing with her dog Dash, or gathering the violets she loved so well. "For ten years", the authoress wrote, "has the public endured to hear the history half real and half imaginary of a half-imaginary and half-real little spot on the sunny side of Berkshire. . . . They turned from the trash called fashionable novels to the common life of Miss Austen, the Irish vales of Miss Edgeworth, and my humble village stories". It would be difficult to exaggerate her importance in the neighbourhood. Her humble cottage used to be a centre of attraction to all the cleverest people in the country. Kingsley from Eversley, Canon Pearson, with his friend Dean Stanley, from Sonning; Mr. S. Landor, Mrs. Barrett Browning, Mrs. Trollope, from Heckfield, and other celebrities, were constantly coming there. When Miss Mitford had one of her famous strawberry parties the whole lane up to her cottage was crowded with the carriages of the rank and fashion of the neighbourhood. It was speedily and universally acknowledged that her exquisite prose idylls constituted a new strain of English classics of the highest description. All around us is the region depicted in Our Village. Every house has its story told of it; every field she made famous. "My beloved village", she exclaimed, and then went on to describe "the long straggling street, gay, bright, full of implements of dirt and noise, busy, merry, stirring little world . . . the winding, up-hill road with its borders of turf and its primrosy hedgerows . . . the breezy common and its fragrant gorse". Miss Mitford led a hard life. She had been brought up in luxury, but owing to her father's extravagance she was turned out of a comfortable home and compelled to take refuge in a tumble-down cottage. From a life of ease she was compelled to turn to one of incessant effort, having to support with her pen, as best she could, a fading invalid mother and a worthless father. She looked at first a plain little person, but a second glance revealed "a wondrous wall of forehead", and she had grey eyes with a very sweet expression. Mrs. Barrett Browning used to say that her conversation was even more interesting than her looks. "Miss Mitford dresses a little quaintly", an American visitor wrote. This was putting it mildly. Mr. Palmer of Sonning mentioned her appearance at a garden party at Holme Park in "a green baize dress, surmounted by a yellow turban". It was also reported that "the turban had the price still hanging on to it". But in spite of her dress her appearance was interesting, and a friend described her as "like lavender, the sweeter it is the more it is pressed". She was also a shrewd observer and sometimes a severe critic. She mostly said and wrote kind things; but, like all pretty purring feline personalities, if stroked the wrong way, her claws could flash out and when they did they were very sharp. Her remarks on public men like Carlyle, Wordsworth, Dr. Vallis and others were very severe. But we must hasten on to our heroine's last resting-place.

In 1851 she deserted "Our Village" and moved to a cottage in Swallowfield, which has little changed since her day. The acacias still bloom beneath which she loved to sit and write. She tells of her migration from the old house to the new: "I walked from one cottage to the other in an autumn evening when the vagrant birds, whose habit of assembling there for their annual departure, gives, I suppose, the name of Swallowfield to the village, were circling over my head, and I repeated to myself the pathetic lines of Hayley, as he saw those same birds gathering under his roof during his last illness: " 'Ye gentle birds that perch aloof Here, in this little home, she received many visits from the lights of literature of her day. Charles Kingsley, from his rectory at Eversley, was the first to come to her, and they were mutually fascinated. She had heaps of friends. James Payn wrote that she seemed to have known every one, from the Duke of Wellington to the last new verse-maker. But the great comfort of her closing years was her friendship with Lady Russell, widow of Sir Henry Russell, second baronet. Nothing could exceed the kindness this lady and her family bestowed upon her. This lightened the dreary hours of illness; and when the end came, and the brave, undaunted spirit winged its way hence. Lady Russell was watching by her side, holding her hand as she sank to rest. One last pilgrimage remains the quiet corner in Swallowfield churchyard where Mary Russell Mitford sleeps beneath a granite cross. The flowers she loved grow around her still. In spite of all her sorrows and hard struggling, her path was always gay with flowers. Nor are we the only pilgrims here. Lovers of Nature, and of that sweet book which she opened wide for them, flock here from America and other lands whither her words have wandered. Thus we leave her, her warm heart resting and her busy hand that wrote so much, lying in peace there, where the sun glances through the great elm trees in the beautiful churchyard of Swallowfield.

Back to 'Byways in Berkshire and the Cotswolds'

|

||

|

Any Feedback or comments on this website? Please e-mail the webmaster |