September

|

Arborfield

|

|

Memories

Related sites:

Full text of

Full text of

|

The Internet has brought an old book back to life by focusing on its contents and not on its title. "Byways in Berkshire and the Cotswolds", by P. H. Ditchfield, M.A., F.S.A., and published in by Robert Scott in London in 1920 is not really about byways at all.

The book is divided into two main parts: The Windsor Forest and the Cotswolds (which until 1974 reached into the west of the old Berkshire), and is a guide-book of many local towns and villages, introduced via itineraries of rambles and boat-trips, full of local history and amusing anecdote. Two of his 'journeys' pass through Arborfield, hence the book's inclusion on this web-site. Peter was so well-connected that he casually mentioned then-famous names such as Prince Christian throughout the book. He made some robust comments on the errors of other historians, particularly on the derivation of place-names such as Arborfield.

Although 'Byways' was published in 1920, it is clear that most of it was written while the Great War was still raging, and so it gives us a rare snapshot into life in the local area during those difficult times. For example, when describing Barkham, he said: "The war has made us a semi-military village and khaki

is seen everywhere. Of the young men, he lamented:

"There is no sight in the world, I suppose, so beautiful, so

wonderful, And of Windsor Forest itself: "It is impossible not to regret the necessity which the war laid upon us for the destruction of our woodlands. Our Windsor Forest has suffered with the rest of the country. The regions of Ascot, Virginia Water and Sunningdale have paid heavy toll to Canadian lumbermen. We have made great sacrifices during the war, and amongst these must be counted the serene beauty of many an English landscape, and the loss of stately trees which none now living will ever see replaced." And closer to home, the woodlands around Eversley, beloved of Charles Kingsley:

"Such is the onward march of the firs which we love to watch in

these days as much as Kingsley did. But the woodman's axe is laying heavy toll

upon our forests. Some seemingly-unkind words about Maidenhead were probably prompted by food rationing in towns in 1917:

"Lately the town has suffered from the advent of aliens from

London,

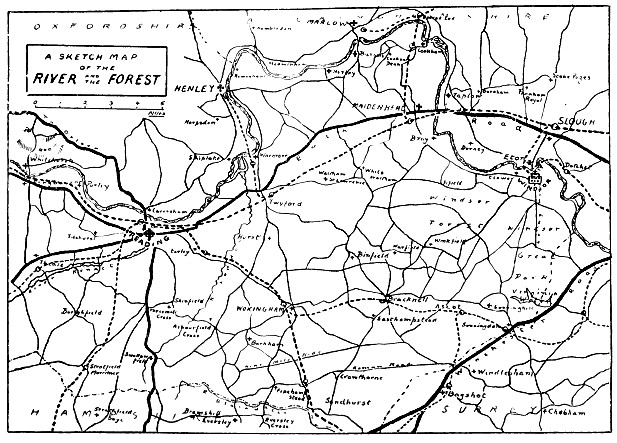

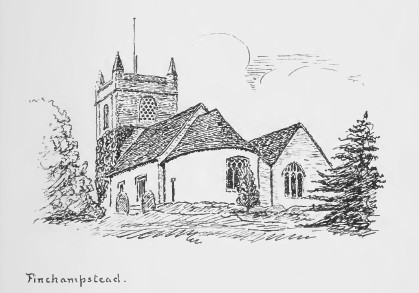

Part 1: Highways and Byways in Windsor Forest Both parts were illustrated by line-drawings and sketch-maps, as shown here:

Here are some quotations from the text:

Chapter 1 - "Windsor Forest": A forest is, according to the dictum of those who are learned in the law, " a territory bounded by unremovable marks, or by prescription, in which beasts and fowls of forest, chase and warren, abide under the protection of the king." According to another authority "it is the highest franchise of princely pleasure." The trees do not make the forest, but the law of the land determined that the forest was set apart for the hunting of the sovereign, and for those who received the royal permission to hunt therein. [P.4] Forests were made to wander in, at least they are so in modern days, when there are no such fearful penalties as loss of life or limb, no horrid mantraps or spring-guns to startle or to maim ; and as a wanderer in this Windsor Forest I claim my right to wander as I list, in history, lore, legend, or topography, and cull what pleases me, disregarding the beaten track so worn by many weary pilgrims. [P.4-5] It extended its sway over parts of Buckinghamshire and Middlesex, nearly the whole of Surrey and the eastern and southern parts of Berkshire, as far as Hungerford, while the Vale of Kennett was deemed anciently to be within its borders. [P.5] He traced the Devil's Highway westwards towards Silchester, and remarked: Sometimes you have to exercise the cunning of a Red Indian tracker to discover this road; in other places it is as plain as a pikestaff. [P.7] It then mounts the hill known as Finchampstead Ridges, though avoiding its steepest slopes. Stop at the summit and admire the view. This is one of the most famous beauty spots in Berkshire, or indeed in southern England. You look over a vast plain bounded by distant hills. At your feet is a deep escarpment clad with pines and firs and heather-clad slopes. Below in the valley of the Blackwater and beyond it rise the Hartford Bridge Flats, along which ran the old coaching road from London to Southampton, much loved by motorists. [P.9] These Finchampstead Ridges benefit by a splendid road made by the late Mr. John Walter, proprietor of The Times, who has left an indelible mark upon this neighbourhood by his benefactions and his buildings; it finishes in a noble avenue, a mile in length, of Wellingtonia pines, fifty-five on each side, forming a grand approach to Wellington College. On these Ridges King Henry VII and his son, Prince Arthur, riding from Easthampstead, set out to meet Katherine of Aragon after her arrival in England to become the prince's bride. [p.10]

To the west of Riseley: Though it has to pass through fields where all traces have vanished, we can conjecture its course by the names Coldharbour Wood, Stamford End, where there was a ford over the Loddon, Stratfield Saye, Stratfield Turgis, and Stratfield Mortimer, the prefix strat signifying street or paved way. [P.13] He quoted both Chaucer and Shakespeare on Windsor Forest, and named the location of "Sir John Falstaff's Oak" [P.20]

Chapter 2 - Forest Hunting: At Cumberland Lodge in Windsor Great Park, he wrote: Here the late Prince Christian, Ranger of Windsor Forest, lived for many years and won the hearts of all Berkshire folk. [P.22] Barkham was central to the Garth Hunt; but here, Peter described stag hunting: Methods of hunting have changed through the ages. When the Royal Buckhounds ceased to exist the carted deer continued in vogue, until the Great War began, with the Berks and Bucks Farmers' Staghounds. At an earlier period the stag was roused from his lair with blood hounds, or harboured by the huntsman or yeoman prickers on foot, and these fleeter dogs of the greyhound type were slipped from their leash for the chase. In Queen Elizabeth's time another method was practised. In Norden's map of the Little Park there is a building called the "Standinge", which seems to have been designed for spectators to watch the pursuit and capture of the stag, and sometimes deer were driven past it and shot with arrows by privileged persons ensconced therein. Queen Bess often indulged in this not very sportsmanlike proceeding. [P.23] But while they lived, the deer were the lords of the forest. Everything was done for their convenience and preservation. Some man who set up a windmill was compelled to take it down lest it should frighten the deer. [P.23]

There is no space for me to record all the lawless deeds done in our forest, the troubles of the Civil War, the slaughter of the deer, the gipsies and other wild people that dwelt in the woods and caught the poor stags with baited apples, the highwaymen who haunted our roads, the "Wokingham Blacks", to whose exploits I may again refer, and finally the enclosure of the forest lands and the vast changes wrought thereby which were by no means all good and beneficial.[P.25] Before we leave the actual forest and its story I must point out sundry bypaths and byways that intersect our district. They radiate like the spokes of a wheel from the Castle as the centre. There is one long road called the Nine Mile Ride, literally nine weary miles in length through the pine woods. These roads owe their origin in the first instance to Queen Anne, called "the Good." She had a passion for hunting, and, as Dean Swift records in his letter to Stella, she used to hunt the stag in summer through the meridian heat, and drove forty miles in one day. Many of them were completed by George III who in his later years could not ride a horse. I believe the Nine Mile Ride was made by him and ends lamely close to a brick-kiln. Malicious tongues often wag about royalties, and it has been said that he had this ride constructed in order to visit the fair Quakeress Hannah Lightfoot; but there is, I believe, no ground for this legendary scandal. [p.26]

Chapter 3 - Binfield and Pope: The old form of Binfield was Benetfeld, and henet or heonet means a kind of coarse grass. From this lowly origin sprang this delightful village with its well-wooded and well-watered pastures, nigh the old road that runs from Reading to Windsor and thence to London. Two hundred years ago, and that was perhaps the period of its greatest fame, it was an attractive place, and since then many large houses have sprung into being, so much so that a former rector, who was somewhat partial to dining out, remarked that he had in his parish thirty-two "soup and fish houses". [P.28]

For the erection of village churches in the days when transit was difficult our ancestors did not import Caen stone from Normandy, or even Purbeck marble, but contented themselves in this neighbourhood with the conglomerate "pudding stone" which they collected with infinite pains and labour when they broke up the " iron pan " of the surrounding heath country. The old squat tower of Binfield church is built of this. [P.29] The late rector, Canon Savory, sent me one day some pieces of an inscribed brass which he had found in a cupboard in the rectory. I at once saw that this was a mutilated long-lost memorial. I consulted Mr. Mill Stephenson, F.S.A., the greatest authority in England on the subject, and the result was the restoration of the brass to the church. It was discovered to be an interesting palimpsest. After the period of the Reformation the brass-makers' shops were filled with old material, spoil from the destruction of the great monastic churches and from the suppression of chantry chapels; these pieces were worked up again into new memorials inscribed upon the reverse side. [P.30] It is noticeable that five tombstones are in memory of Roman Catholics who lived in the reign of Charles 11. One has the letters C.A.P.D., a disguised form of the favourite pre-Reformation prayer Cujus Anima Propicietur Dens. Evidently there was a colony of Roman Catholics at Binfield at the end of the seventeenth century, and amongst these were members of the Dancastle family. The last of the race died in 1780, "after patiently enduring the most excruciating pains of the gout without intermission for upwards of sixteen years", as a tablet to his memory in the church records. It was owing to two brothers, John and Thomas, scions of this house, that Alexander Pope, the father of the poet, came to reside in the village, which thus became the home of the famous writer during his early years. [P.32-3] Pope described his home as : My paternal cell He tells how his father spent the time in gardening, and how he Plants cauliflowers and boasts to rear His Windsor Forest has been described as " a beautiful incongruity." He speaks of the Inspiring shade, Yet he talks of the pines diffusing "a noxious shade," and of the "dreary desert," and the "gloomy waste," and finally Crowns the forests with immortal greens. [P.37]

Chapter 4 - Wokingham, a Forest Town. Having moved from Binfield to nearby Warfield, he says: Our faces are set towards the old Forest town of Wokingham, and here I may note the changed condition of the country. In former times it was wild and desolate, with long stretches of heath and few roads. Hence it was not difficult for travellers to lose their way at night time. So Richard Palmer, a good benefactor of Wokingham, in his Will dated April 12, 1664, bequeathed a rent-charge on a piece of land in the parish of Eversley for the purpose of paying the sexton to ring the greatest bell in the church for half-an-hour every evening at eight o'clock, and every morning at four o'clock, or as near those hours as might be, from the 10th of September to the 11th of March for ever. The object of this ringing was to encourage a timely going to rest in the evening and an early rising in the morning, and to be a timely and pious reminder of the hearers' latter end, inclining them to think of their own passing bell and day of death, while the morning bell reminded them of their resurrection and call to their last judgment, but also in order that strangers and others, who should happen in winter nights within hearing of the bell to lose their way in the country, might be informed of the time of night and receive some guidance into their right way. That bell is still rung in the evening, but not in the morning, though quite recently the benefaction was actually lost. [P.41-2] We will not take the main and quickest road to our destination, but wander on from the cross-roads nigh the "Stag and Hounds Inn" to the "Hare and Hounds Inn", a favourite meet of the Garth Hunt, where a turning to the right leads to a beautiful park and house called Billingbear. Anciently the manor belonged to the See of Winchester and was surrendered to King Edward VI in 1551, who granted it to Henry Neville, gentleman of the bedchamber. These Nevilles were an ancient and illustrious family. They held possessions in the Forest from Saxon days, and for hundreds of years were "Keepers by inheritance". In addition to Billingbear they held the whole Bailiwick of Fiennes, an extensive district, including Bray, Winkfield, Bracknell and Wokingham, the manor of Wargrave, and Henry Neville was recommended by the King for Sheriff of Berkshire. [P.42] Henry Neville was a staunch supporter of the New Learning and the Reformation, and rose to particular favour with Edward VI. When Mary came to the throne these grants were annulled, but under Queen Elizabeth he rose again into still higher favour, was knighted and restored to his estates. He was very zealous in persecuting Recusants, [P.42] Soon the ancient forest town appears in sight. Modern houses and villas on the outskirts seem to dispute its claim to antiquity, but the view of the grand old church standing out from its encircling trees removes any doubts that might arise. Some years ago it narrowly escaped demolition, but was happily saved by the zeal of the parishioners. [P.44]

Leaving the church we pass along Rose Street, the oldest part of the town, with charmingly picturesque half-timbered sixteenth century cottages, and then reach the market place. The present unsightly Victorian Town Hall, erected in the 'sixties, took the place of an interesting earlier building with an undercroft, supported on pillars, wherein the business of the old municipal town was transacted. It is surrounded by some old houses. On the east next to the "Bush Inn" stood the "Old Rose Inn", concerning which some stories are told. The present "Rose Inn", a picturesque old building with its narrow passage into the inn-yard, not exactly adapted for a coach and four. It is a very charming old-fashioned hostelry, and much frequented in modern days. The old "Rose" on the east side of the market place had cause to blush on one occasion when some wits of the day, Gay, Swift, Pope and Arbuthnot, were detained there by the wet weather, and amused themselves by composing a song in praise of the charms of Molly Mogg, one of the daughters of the landlord, John Mogg. She had a sister named Sally, who was also a handsome beauty. Molly was much admired by the young squire of Arborfield, Edward Standen; but she treated his attentions with scorn and refused to marry him. The wits, observing his melancholy manners, composed a poem in praise of Molly. Each poet contributed a verse as they sang of the disconsolate lover: His brains all lost in a fog Edward Standen was the last of his race, and is always said to have pined away and died at the early age of twenty-seven. Every account of Wokingham records this supposed fact. It is unpleasant to be obliged to dispel illusions. However, I have studied the pedigree of the Standen family of Arborfield, and find that this Edward Standen married a lady named Eleanor, and therefore consoled himself after his youthful disappointment. He died childless. Molly lived to the age of sixty-seven and died unmarried. Some have supposed that Sally was the scornful and reluctant maid who won the affections of the young squire, but I refuse to dethrone Molly from her rightful place. (Mr. Vincent in his Highways and Byways in Berkshire is hopelessly muddled about Edward Standen, Miss Mitford and Molly Mogg. When Miss Mitford refers to the ruined state of the house about twenty years prior to her writing Our Village, she was telling the sad story of the Dawson family, not of the Standens. Mr. Vincent seems to have been in entire ignorance of the descent of the Manor, and of the Reeves and Dawsons who held it after the death of Mrs. Edward Standen. Edward Standen's Will is at Somerset House and was proved by his wife, sole executrix, April 7, 1731. One seldom finds so many errors in a single page as in Mr. Vincent's story.) He then describes the blood-thirsty scene at the annual bull-baiting that lasted into the 1800s. [P48-9] and concludes with this anecdote: At the close of the day, when drink had made men "full of quarrel and offence," there were disputes and fighting and rough horseplay, and in the Parish Registers there is a tell-tale entry, "Martha May, aged 55, who was hurt by fighters after Bullbaiting, was buried December 31, 1808," As early as 1801 a sermon was preached in the parish church of Wokingham on "Barbarity to God's dumb creation," containing a severe condemnation of the ancient practice, but it was not until St. Thomas's Day, 1832, that the last baiting took place. The bulls are still slaughtered, but in a more merciful fashion, and the meat given to the poor. [P.51] Continuing the barbarous theme: If you go beneath the archway of Mr. Sale's shop which was formerly an inn, you will find at the end of the passage a footpath that bears the name "Cock Walk", and in what is now a potato ground in former days was a famous Cock Pit. Here thousands of pounds were won and lost in backing the rival birds. Here the gentlemen of Berkshire and Hampshire had annual contests, and I have seen in the columns of the Reading Mercury, one of the oldest newspapers in the kingdom that still survives, advertisements of these contests with minute laws and regulations governing the sport. [P.51] Moving on to justice: As Wokingham was a Forest town, the Forest Courts were held there, or at Windsor, for the Berkshire portion. The justice of the Forest, or his deputy presided, and the inquisitions were made before him by the various Forest officials, such as the warden or chief forester, the foresters, verderers, regarders and free tenants. In the Public Record Office there are a large number of these inquisitions dating from 1363 to 1375. [P.52] The origin of the name Wokingham is worth noting. A century ago the inhabitants thought that the name was connected with the oak tree, and spelt it Oakingham. In earlier maps it appeared as Okingham or Okyngham, but in its earliest form it is printed Wokingham (cf. Feudal Aids and Close Rolls). The prefix Wokinga is the Anglo-Saxon genitive, plural Woccinga, and means the sons of Woce, and ham in this case means "home"; hence the place-name means " the home of the Woccinga or sons of Woce, a Saxon settlement of a family which also left its name behind at Woking in Surrey. [P.53] Leaving the Town Hall a pleasant footpath leads to Lucas's Hospital, a very charming building, consisting of a central portion and two wings, and founded by Henry Lucas by his will dated June 11, 1663. It was placed in the custody of the Drapers' Company of the City of London. The east wing is occupied by a chapel, the west wing by the master's lodging. There is accommodation for about fifteen old men to be selected from divers parishes in Berks and Surrey. The Hospital looks very calm and peaceful, especially on a summer's evening when the old men are sitting in front of their beautiful home. [P.55] In the Broad Street there are several good eighteenth century substantial houses with fine gardens at the back, and nearly opposite to St. Paul's Church there is an old manor house called the Beches. It takes its name from Robert de la Beche, who belonged to the old family of the de la Beches of Aldworth, who gave their name to Beach Hill [sic] near Mortimer. [P.56] I must not pass over one other side in the life of the town, though it does not bring it much credit. It must be confessed that in times not very far remote we were rather a lawless lot. For generations, for centuries, the inhabitants of our forest have been deer-stealers, poachers, coney-catchers and trappers. Some of the elite of the profession of highwaymen have exercised their calling upon the borders of Berkshire and within the county itself. The great moor between Wokingham and Bagshot was the favouiite haunt of the owler, the footpad and the highwayman. [P.56] Life in our country town is usually very peaceful and placid, but in recent years some building estates have been developed, and the old town hardly recognizes itself. However, it has not lost its calm or its charm, and there are many worse places that one might choose for one's home than the good old Forest town of Wokingham. [P.58-9]

Chapter 5 - From Wokingham to Maidenhead Leave Wokingham by the northern by-lane opposite St. Paul's Church, a fine modern building erected by the late generous squire of Bear Wood, Mr. John Walter, his architect being Woodyer. Passing the Holt, a much modernized seventeenth century house, and Bill Hill, the residence of the Leveson-Gower family, and arrive at Hurst, a long, straggling, delightful village with a picturesque old church and almshouse. [P.60] A remarkable feature of the old houses in the neighbourhood is the small extent of the estates which in olden times belonged to them. The probable reason of this is that the early occupants were connected with the court at Windsor, as secretaries, cofferers, etc., and the occupation was residential, not territorial; and these grants of estates being in the Forest, were not allowed to be large lest they should interfere with the hunting and the deer. [P.61] The existence of so many places called Hatches shows the old internal boundaries of the Forest. [P.61] A favourite name for inns in the Forest district is the "Green Man" — there is one in Hurst —where the greenclad foresters used to refresh themselves when they were hunting or minding the deer. [P.61] Indications of former ownership by the Crown are sometimes discovered under the bark of trees when they have been cut down. I have seen the marks of the royal crown grown to a large size with the growth of the trees on some of the beeches, after they had fallen, in Mr. Walter's Park at Bearwood. [P.61] He describes the long history of the Castle Inn, formerly the Church Inn, and quotes from Aubrey as follows: "In every parish was a church house, to which belonged spits, crocks, and other utensils for dressing provisions. Here the housekeepers met. The young people were there too, and had dancing, bowling, shooting at butts, etc., the ancients (i.e. the old folks) sitting gravely by, and looking on." [P.63] From Hurst we could make our way to Sonning, one of the prettiest villages in England, situated on the Thames with an old bridge across the river. It is a very ancient place, and was the ecclesiastical centre of the district, as I have already remarked. It contained an episcopal palace where in mediaeval times the Bishops of Salisbury resided, and previous to the formation of the Sarum See the Bishops of Ramsbury and Sherborne who were sometimes styled Bishops of Sonning. [P.63] Regarding the church building at Ruscombe: A local antiquary was once expatiating upon this tower and on the excellence of its architecture, and said, "The parishioners are very proud of this tower, seeing that it was built by a very famous architect whose initials are in the vane, C.R., Christopher Ren!" [P.64] From 1710 to his death in 1718 William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, lived at Ruscombe, and thus brought undying fame to the village. The house in which he resided was pulled down by General Leveson-Gower in 1830. That was unfortunate. If it had been left standing and turned into a Penn museum, thousands of American pilgrims would have flocked to Ruscombe to worship at the shrine of their great countryman. [P.65] We might continue our journey northward across open country to the pleasant river-side village of Wargrave, the old church of which fell a victim to the insensate rage of the suffragettes and was entirely burnt down just before the war. A fine new church has arisen from its ashes. [P.65] But we will continue our present journey from Ruscombe in an easterly direction to Waltham St. Lawrence, where is the old "Bell Inn", a coaching hostel, a fine gabled halftimbered building standing opposite the village pound and a much restored church, but it retains much that is interesting. [P.66] Moving on past Shottesbrooke to White Waltham: Just outside the church wall the old stocks and whipping post remain, memorials of old-time punishments. [P.73] Travelling two miles from White Waltham we are on Maidenhead Thicket, a famous ground for highwaymen and footpads. Stretches of beautiful common covered with gorse extend on each side the road. It was a tract so infested by robbers that as early as 1255 an order was issued for widening the road between Maidenhead Bridge and Henley-on-Thames, by removing the trees and brushwood on each side. [P.73-4] That the thicket was a sufficiently dangerous locality, Leland shows in his account of his journey from Maidenhead to Twyford. For two miles the road was narrow and woody, dangerous enough; then came the Great Frith three miles long; altogether a wood infested with robbers five miles in extent. "And then", he says, "to Twyford, a praty tounlet a two miles." Twyford was undoubtedly a charming spot to reach after a route so long, tedious and dangerous. [P.74]

Chapter 6 - Maidenhead and Bray WE are told that Maidenhead cannot boast of a long or stirring history, and that it is but a child of its older neighbours, Cookham, Bray and Taplow. If so, it is a somewhat sturdy infant, and has thriven amazingly in recent years. [P.76] The birth of Maidenhead may be attributed to the building of the bridge. Previous to its erection the nearest crossing of the Thames was by a ferry at Balham, and the great western road to Reading, Gloucester and Bristol went through Cookham. After the building of the bridge the traffic was diverted from Burnham and Cookham and caused Maidenhead to increase in prosperity and importance. Camden says that after the town " had built here a bridge upon piles it began to have inns, and to be so frequented as to out-vie its neighbouring mother, Bray, a much more ancient place". The first bridge was built about 1280, so that it can claim a long history. [P. 80] Peter Ditchfield even criticised Camden's historical precision. Camden said that the bridge was built in 1460, but that there's documentary evidence that the bridge was repaired in 1297.

As was not unusual in medieval times a chapel was connected with the bridge. Old bridges were rather perilous structures, and travellers would often wish to pray for a safe passage, or to give thanks for their secure crossing. [P.81] There is little of interest in modern Maidenhead to attract the attention of the lover of old buildings. Some old almshouses on the road to the river were erected in 1653. [P.83] All the churches are modern. But those who love the river know well the town's attractions, and the charms of that fine reach within sight of the Cliveden Woods or Burnham Beeches, though their delights may be dimmed by the scramble through the famous and fashionable Boulter's Lock. [P.84] The village [of Bray] will be associated in the minds of most readers with the turncoat vicar, whom Fuller describes as living in the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth", first a Papist, then a Protestant, then a Papist, and then Protestant again. He had seen some martyrs burnt at Windsor, and found this fire too hot for his tender temper. This vicar being taxed by one with being a turncoat and an unconstant changeling: 'Not so,' said he, 'for I have always kept my principle, which is this, to live and die the Vicar of Bray.' Such many, nowadays, who, though they cannot turn the wind, turn their mills, and set them so that wheresoever it bloweth their grist shall certainly be grinded." [P.87] Peter suggests that the traveller returns to a hostelry in Maidenhead for the night, which gives him a chance to relate an amusing story about the "Bear", where James I dined with the Vicar and Curate of Bray unbeknown to them. For the punch-line, see P. 95].

Chapter 7 - From Maidenhead to Henley. A PLEASING diversity in our methods of travel may be made by taking a boat at Maidenhead and traversing the old Berkshire highway, the river Thames. In summer the excursion can be made by the Thames steamboats which allow of landing at any lock and at frequent points elsewhere. In olden days before railways were invented and the system of canals extended, the Thames was the principal means for transit of goods and the great highway of traffic. In 1205 King John gave licence to William FitzAndrew to have one vessel to ply on the river between Oxford and London, without any impediment to him or his men on the part of the bailiffs of Wallingford and Windsor, and all through time following the Thames has been thus used. In the time of Henry VIII both persons and goods were usually conveyed by boat from Windsor to London. "The quality" travelled by barges, their servants and goods by boat. [P. 95] The Thames has always been liable to flood, but he quoted a Dr. Plot who stated that in summer "in dry times barges do sometimes lie aground three weeks or a month or more". From Maidenhead, the voyage in a rowing-boat takes him past 'Cliefden' to Cookham, whose ancient church is described in "a long and interesting paper by Sir George Young" - an ancestor of the current MP. The townlet has many attractive-looking Queen Anne houses and halftimbered tile-roofed cottages, but its old-world character has been lost in modem times, the motor-horn is heard continually in its streets, and crowds of excursionists from London invade this once retired village. [P.97] Further upstream, past Bourne End and Little Marlow, he complains that Great Marlow has a "hideous modern church that took the place of a fine Gothic one in 1835". [P.98] On the other hand, upstream is: Bisham Abbey where we could linger with pleasure the whole length of a summer day. The beauty of the scenery and the historical associations of this monastic house and architectural charms, are delightful in the extreme. Embarking again, another mile

We embark again, and soon another monastery appears in sight upon the Bucks shore, the famous Medmenham Abbey, famous not only for its monastic establishment, but infamous, too, for the orgies of that mad company of pseudo-monks who carried on their revels here in the eighteenth century. [P.103-4] The fraternity was known as the "Hell Fire Club". It is perhaps as well that most of their proceedings should be buried in oblivion. Their rites have been described as "Bacchic festivals. Devil worship, and a mockery of all the rites of religion". They slept in cradles, and one that belonged to John Wilkes is still in existence. They used to stay at Medmenham for a week and assemble twice a year. [P.105] Of Henley, Peter says it used to have a castle, and continues: An examination of the documents of the corporation, which date back to 1397, proves that Henley was at one time a walled town. It was situate in the kingdom of Mercia, while the county of Berks on the other side of the river was in Wessex. No one has yet discovered how old the corporate life of Henley really is. The ledger book dates back to the reign of Richard II [P.107] Henley has many hostelries which in time of peace when the Regattas used to be held, and during the long summer days when house-boats congregate on the Thames fair banks, are full of guests. Chief of them is the old "Red Lion Hotel", which has a famous history. It was an old coaching inn; into its yard in the palmy days of coach-traffic a score of these vehicles drove every day. [P.109] We return to our Forest town, Wokingham, through Wargrave and Twyford, and after a good night's rest at the "Rose" we will start again on our pilgrimage and explore further our Forest district. [P.111]

Chapter 8 - Wokingham to Miss Mitford's Country - The entire text is transcribed here.

Chaper 9 - Swallowfield, Eversley and Kingsley's Country - The entire text is transcribed here.

Part II - "Berkshire Highways and the Vale of the White Horse" Most of this section of the book isn't close to Arborfield, but the first journeys in Part II were within walking distance, albeit half a century before the motorway and dual carriageways completely transformed the scene.

Chapter 1 - from Three Mile Cross to Reading. WE hasten back to Miss Mitford's early home at Three Mile Cross, and take the road to Reading. As the name of the hamlet implies it is a good three miles' walk or cycle ride to our county town. It is a road I know well. In the course of my clerical duties I have walked 2,000 miles along it, and used to know every stone, and house and man, woman and child and dog who lived there. Miss Mitford's company will be better than mine, so we will stroll with her along this road to the town she calls Belford Regis, which is none other than Reading. She wrote a very fascinating book called Belford Regis, which every one who loves glimpses of old-fashioned English life at the middle of the last century should read. It is full of her playful humour and gentle satire, a book that creates smiles and sometimes sighs. [P148] Reading is a progressive town, a busy modern place, that fills the world with biscuits, that sends its seeds into all countries, that has iron-works and printing works and tin works, and is gay and prosperous except in war-time. It pulls down its old houses and builds greater. [P.150]

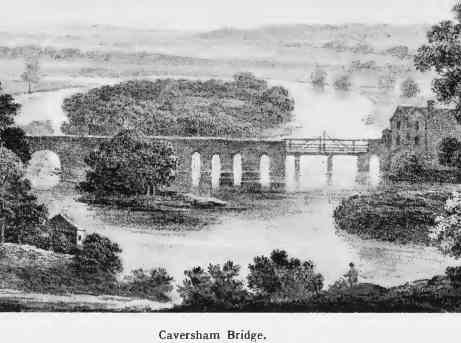

Chapter 2 - from Reading to Streatley by the Thames Highway. Caversham Bridge is also renowned in story. A view is shown of the ancient bridge that existed here before the present hideous iron structure was erected in 1870. The old bridge was very narrow and inconvenient: two vehicles could not pass each other. A sharp skirmish took place on this bridge and on the hill by the church, resulting in the defeat of the Royalist troops who were attempting to relieve Reading. [P.155]

Proceeding up-stream we behold some of the richest scenery in the Thames Valley. Past the "Roebuck Inn", where the Oxford Eight used to train sometimes in the good old days before the sounds of war killed the splash of oars, we come to Purley on the Berkshire bank, surrounded by immemorial elms beneath the shadow of the woods of Purley Park. [P.156]

Part III - "Where Three Counties Meet"

Part IV - "The Cotswold Country"

Back to Peter Ditchfield Family page

|

||

|

Any Feedback or comments on this website? Please e-mail the webmaster |

Its author, the Rev. Peter Ditchfield, knew Berkshire well. Having

been a curate at Sandhurst and at Christ Church, Reading, he was

Rector of Barkham Church from 1886 until his death in 1930. He was a

prolific author, writing many books on diverse subjects. He also wrote 'Notes

and Queries' for the Reading Mercury for many years, and was president of

Berkshire Archaeological Society.

Its author, the Rev. Peter Ditchfield, knew Berkshire well. Having

been a curate at Sandhurst and at Christ Church, Reading, he was

Rector of Barkham Church from 1886 until his death in 1930. He was a

prolific author, writing many books on diverse subjects. He also wrote 'Notes

and Queries' for the Reading Mercury for many years, and was president of

Berkshire Archaeological Society.

and a half brings us to

another monastic institution, Hurley Priory, of which the vicar, the Rev. F. T. Wethered, is the able and learned historian. He has examined endless documents

and his work is a mine of antiquarian lore. Few villages can rival Hurley in

interest. It has a number of half-timbered cottages; the dovecote of the

monastery, the remains of that institution including the church, and the

historical associations of Lady Place, constitute an extraordinary number of

special attractions, and the village is fortunate in possessing such an

enthusiastic and able historian. [P. 101-2]

and a half brings us to

another monastic institution, Hurley Priory, of which the vicar, the Rev. F. T. Wethered, is the able and learned historian. He has examined endless documents

and his work is a mine of antiquarian lore. Few villages can rival Hurley in

interest. It has a number of half-timbered cottages; the dovecote of the

monastery, the remains of that institution including the church, and the

historical associations of Lady Place, constitute an extraordinary number of

special attractions, and the village is fortunate in possessing such an

enthusiastic and able historian. [P. 101-2]