|

Arborfield

|

|

Properties

Related sites:

Full 1944 Aerial Photo from Carter's Hill to Winnersh Close-up Aerial view of Arborfield 'Starfish' site More detailed description of 'Starfish' sites Note: ----------------- |

The Decoy Airfield that Wasn’t Over several years, there have been rumours that there was a decoy airfield during WWII in the grounds of Arborfield Hall. At last, we now have the facts. There wasn't an airfield, but there was a decoy site known as a ‘Starfish’. These decoy sites were so top-secret that they remained classified for decades after 1945, so it’s no wonder that stories are confused. A book written in 2000 entitled ‘Fields of Deception’ tells the whole story about the decoys – and may jog some local memories. If so, please let us know!

The book gives scant detail about the Arborfield site

(one of

three protecting Reading), but it does have an aerial photograph clearly

showing where Arborfield’s was located, plus a second aerial photo of

another of the three sites, at Sulham. The detail of the Starfish site shown on the right was taken from a USAAF aerial photo of Carter's Hill and Winnersh, dated 8th March 1944, ref. 5045, reproduced by permission of National Monuments Record, English Heritage. Click on the picture for a larger image. The idea of decoy airfields and other pieces of deception was tried out with some success in the Great War, but the lessons were soon forgotten. It wasn’t until the late 1930’s that something was done to repeat the process. The film-maker Alexander Korda of Denham Studios was one of the catalysts in planting the idea, but it was another film-maker, Norman Loudon and his Sound City Films of Shepperton, who turned the idea into reality, or at least make-believe. Colonel John Turner was the ideal person to mastermind the whole scheme. After a distinguished career in the Army, he had worked as the civilian Director of Works and Buildings at the Air Ministry in the 1930’s, setting up real airfields, and he retired just before WWII started. He was head-hunted and agreed to lead the new secret department back at the Air Ministry in the Strand. For some years, it didn’t even have a name. Even at his death in 1958, his Obituary didn’t mention his role. Of course, the film industry was highly skilled at deception, and it was able to turn out reasonable copies of Hurricane fighters and Wellington and Whitley bombers which looked realistic from the air. It was able to mimic the ‘satellite airfields’ that were set up close to the main fighter and bomber airfields, and it created some highly-effective special effects to deceive night-time flyers. What kinds of Decoy were there? The first decoys were classed as ‘K’ – the daytime dummy airfields. They were initially successful in drawing enemy fire away from the real airfields, but it was soon apparent that they couldn’t fool the Luftwaffe for more than a year or so. They required a lot of manpower to maintain the effect – by turning the dummy aircraft through 90 degrees and moving them around the site to give the impression of activity; by racing lorries along imaginary runways to display the marks of take-offs and landings. Far more effective were the night-time decoys – the ‘Q’ sites. They had electric lights to mimic the glide-paths of real airfields, and if a ‘friendly’ aircrew was deceived into attempting a landing (which often happened), the lights had to be extinguished quickly. By day there was little to see. There’s no evidence that the Arborfield site was either a ‘K’ or a ‘Q’ at any time. Warfield (Grid reference SU 863744) was the nearest example of a ‘Q’ site. There were elaborations on the ‘Q’ theme to represent factories, railway marshalling yards and docks, and to mimic the effect of incendiary bombs with fires, but there was no need for anything on this scale in Berkshire. By November 1940 there was a need for ‘SF’ or ‘Special Fire’ sites to draw bombers away from major towns and cities. Eventually they became known as ‘Starfish’ (from the letters 'SF'), and this is what was created in Arborfield. Each site would have a variety of special effects primed by electric fuses, to be brought into action as soon as a raid was anticipated. While the rest of the countryside was blacked-out, tell-tale signs of light would appear at the decoy sites, and as soon as incendiaries were being dropped, the fires would start. Reading was number 29 on the list of towns and cities to get ‘Starfish’ protection, and its first site would have been ready in early 1941: SF29(a) Binfield SU

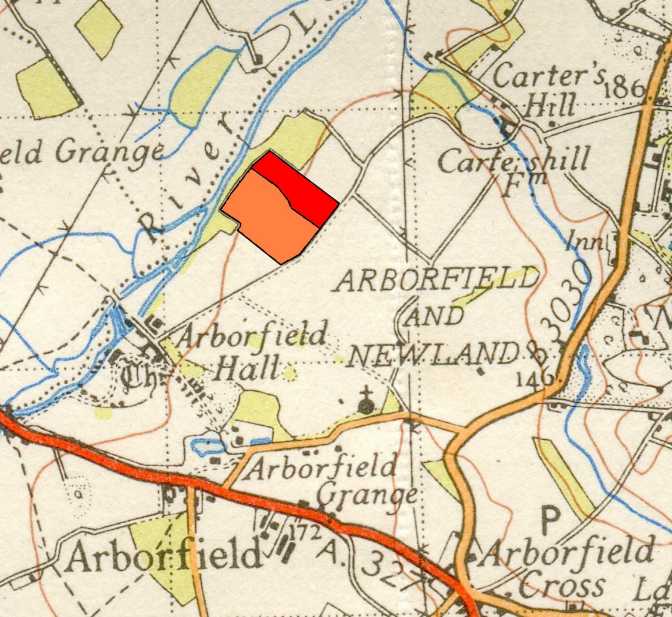

831732 We now know from the National Archives that both the Binfield and Arborfield sites were operational until November 1944, but Sulham was probably decommissioned before then. Here's the Arborfield site in two shaded areas super-imposed on a 1940's Ordnance Survey map. It is in two parts, the northern one being the main operational area: The aerial photo of Arborfield from 8th March 1944 shows that there were many clusters of ‘Basket Fires’ in the main operational area. These were typically 3 ft. square wooden crates on legs, lined with wire netting and filled with layers of highly flammable but cheap materials such as scrap wood, shavings, sawdust and pine clippings, with a gallon of creosote spread between each layer. Covered in netting and hessian and topped with roofing felt, there would be dozens arranged in groups. When ignited, they would look from the air like houses on fire. Most would be ready to ignite electrically, but adjacent ones would catch fire as the conflagration spread – aided by ‘flare cans’ containing 4 gallons of creosote linked to the cages with wicks. The effect would last well over an hour. Three other main classes of fire were: ‘Crib Fires’ – large cages with flare cans underneath, with a layer of firewood and topped with coal, to give a longer burn – up to 4 hours. ‘Boiling Oil Fires’ – heavy steel troughs with half a ton of coal mixed with creosoted waste, topped with steel trays. Diesel or gas oil would be fed from one tank, while water would intermittently be fed from another to give a varied pyrotechnic display. ‘Grid Fires’ – a header tank of liquid fuel would be sent down a sprinkler pipe to a grid of fire elements stretched over about 12 yards, and producing a vivid yellow flame. The site needed to be at least 800 yards from settlements – and the one at Arborfield, almost exactly on the northern part of the Bernard Weitz dairy research centre at Hall Farm, was well away from both Arborfield Cross and the cluster of buildings around the Hall, though quite close to Hall Farm house and Carter’s Hill Farmhouse. Some Starfish sites were spectacularly successful; those around Bristol and Portsmouth attracted many bombs and undoubtedly saved these cities from greater destruction. Others were not so good, for various reasons. We know that Reading passed through the war relatively unscathed, so there may not have been much need to fire its Starfish sites. If they were set ablaze, the villages would have seen a dramatic display when visiting their ‘privies’ at the bottom of the garden… The Starfish sites needed a complement of 24 personnel to operate fully and to be prepared for re-use soon after being fired. Overall across the U.K., decoys of all types probably deflected over 2,000 tons of bombs. It worked out into several thousand lives saved during the course of the war. Arborfield’s site was ready and waiting to do its part until at least the middle of 1944 when we had air superiority, after which the enemy action switched to Flying Bombs, making the decoys redundant. For more details on the various Decoys, visit these web pages:

BBC ‘Matter of Fact’ programme notes The book ‘Fields of Deception’ is a detailed reference work by Colin Dobinson (Methuen, 2000. ISBN 0 413 74570 8) Our trawl through the archives at Kew revealed how a typical Starfish site would be set up, how Arborfield amongst others in the south and east of England were converted to be able to provide a 'Minor Starfish' fire, and how a typical Starfish site would be de-commissioned. Click here for this extra information.

|

||

|

Any Feedback or comments on this website? Please e-mail the webmaster |