|

Arborfield

|

|

Ernest Dormer wrote the 'Notes and Queries' history series in the 'Reading Mercury' during the 1930s, continuing the tradition set by his predecessor Peter Ditchfield . Ernest had contributed articles on the history of Arborfield and the Old Church since at least 1907, and continued with the historical column until his death in 1940, aged 75. On March 17th 1934, Mr. Dormer speculated about the future growth of Reading, imagining its boundaries 50 years hence. He had no knowledge of any plans for a motorway south of Reading, and expected the 'city of Reading' to have reached the northern border of Arborfield by 1984. Actually, the M4 effectively marked the southern boundary of greater Reading until around the end of the 20th century, but this has now been breached with developments in Shinfield village. The 'Reading Mercury' was already reporting on the troubling events in Germany, and inviting its more affluent readers to take a special Thomas Cook's tour to see the country for themselves. It had also reported on Fascist meetings in Reading, and carried readers' letters on the desirability or otherwise of dictatorship in the U.K. Of course, the coming World War affected Reading's growth for a couple of decades, as hinted by Mr. Dormer at the end of the essay. A legacy of WWII was the designation of Heathrow as London's airport; international airliners regularly 'stack' above Woodley Beacon, awaiting their turn to land when the wind is blowing from the east. Woodley Aerodrome was a major airfield for training and aircraft manufacture during WWII, but although several of the buildings still exist, the airfield has long since been covered with factories and houses. Here is the article (with a few added illustrations), plus a couple of others from the 'Reading Mercury' from the early 1930s. - With acknowledgements to Berkshire Media.

WHITHER READING? “A Great City of the South.” CATHEDRAL CHURCH AT SONNING? By ERNEST W. DORMER, F.R.Hist.S. It must be obvious, even to the casual observer, that the Borough of Reading is entering upon another of those forward movements which have marked its growth from an agricultural to an industrial town in the last hundred years. No one can walk through Broad Street without being conscious of a vitality which was not apparent even ten years ago. And if we go back forty years the advance is startling. It is not that the population is noticeably increasing – Reading has not reached the hundred thousand mark yet – but there are cumulative signs that speak of an increase in business and a rapid extension of the area which the town, by its geographical situation, is designed to serve. Rural remoteness is now a thing of the past; accessibility to main centres easy and comfortable. And this conscious animation in Reading is not wholly due to the advent of commercial enterprise, of national rather than local origin, which has come to speed the advance in the centre of the town. For some psychological reason not easy to fathom, Reading has always grown to the south and west with more willingness than in any other direction. The ancient Hundred of Reading lay mainly to the west and the north-west; and the early settlement certainly had no interest in the east. Reading was a Kennet town and a hedge and a ditch for possibly over a thousand years were sufficient to separate it from the manors of the great ecclesiastical overlords on the eastern side. But in 1911, a more spectacular thrust was made to the north, and the ancient boundary of Wessex and Mercia was crossed. Moreover, what is sometimes forgotten by the man in the street, part of the County of Oxford was bitten out and added to the County of Berks. It may appear to some surprising that the more formidable natural boundary of the Thames should have been crossed in preference to an easier and arbitrary boundary on the east and south-east, but to those who move in the technical domain of rateable values and borrowing powers the explanation is a simple one. PRESENT DEVELOPMENT A BEGINNING. And this specious explanation probably accounts for the previous move of 1887 to the south and west and the partial intake of Earley, when only half a mile or so to the east and a little more to the south-east were added by that extension. But building had already proceeded apace on the northern side of the main London road beyond the Marquis of Granby, anciently the Gallows Tavern , and the Earley Rise and Mockbeggar estates were in process of a development similar to that which now marks other areas in the same neighbourhood. Some weeks ago there appeared in the Press a series of excellent photographs showing what is already happening in Earley. It is clear that this is only a beginning, but it is symptomatic of a mighty movement which has gripped many a field and meadow and orchard on the Great West Road beyond Colnbrook , and we are being forced to the conclusion that Reading is nearer London than its mileage connotes. The giant octopus is throwing out its tentacles in an alarming manner. When the next borough extension comes, what are the areas likely to be incorporated and what are the historical details which will help to swell the dossier of him who writes a history of Reading half a century hence? Let us attempt the journey and, as it were, beat the imaginary bounds of that future city. The extension of 1887 took in on the eastern side parts of two ancient manors – Earley St. Bartholomew and Earley St. Nicholas. Included was a portion of the old Common Fields of Earley, which had remained for probably a thousand years within the bounds of this liberty. The Southern railway, from near the Kennet mouth, provided a simple, ready-made line of demarcation as far as Church Road, Earley. I do not propose to labour the historic interest of this small section, as I have frequently dealt with it in these columns, but I would repeat an observation I made some time ago when dealing with the site of a forgotten wharf at the confluence of the two rivers , that the liberty appears to have been a buffer state between a rural demesne and an ecclesiastical lordship, and its separate mention in Domesday Book may be taken to indicate an important settlement quite independent of Reading or Sonning. Its extensive Common Fields would seem to point to a much greater population than were resident here in post-medieval times. SOME FIFTY YEARS HENCE. But let us try to visualise the new Reading of some fifty years hence. Our bounds can only be approximate and the area to be incorporated in the next great drive to the east, south-east and south may prove to be incorrect in parts, for many considerations have to be taken into account when owners of land are called upon to share the cost of urbanising a rural district. It is as well to have a point d'apput, and we will take Loddon Bridge, on theWokingham Road .

Whatever happens either side of this ancient crossing, the extended borough will have to reach to here. In doing so it will incorporate parts of two existing parishes, Earley and Woodley, for the boundary between these two liberties crosses the main Forest Road at a spot near Hungerford Lodge . Now let us take another point of contact: Spencers Wood, on the southern or Basingstoke Road. The Loddon crosses the road at Swallowfield Mill, and on the northern side of the river we are in Shinfield parish, parts of which abut on Reading near the Merry Maidens Inn. It is obvious that there would be a huge absorption if the Loddon is to bound the new Reading between Swallowfield Mill and Loddon Bridge, but the fact remains that rapid development is proceeding, or will proceed, on many of the sites in this neighbourhood, which are not too low-lying.

The erection of houses, moreover, is not now an isolated undertaking; they are now building by the hundred; and the syndicate has taken place of the individual. The problems of water, sanitation, education, lighting and the many amenities of a borderline urban population will have to be faced in the not very distant future. And no town contemplating expansion can ignore those “lungs” which modern civilisation has now decreed to be a necessity rather than a luxury. But a less ambitious project may suffice on the south and south-east, and in this event we could take a road running east and north through Hyde End and School Green, after which there would be a choice either by the Parrot Farm road to the Loddon again and thence to Loddon Bridge, or going a little further north, along Cutbush Lane, taking in much of Lower Earley and thence via Mill Road and Loddon Mill [Sindlesham] to the bridge. THE MUNICIPAL AERODROME. We are now back to our point d'apput and will proceed north-east. There is a very old road leading from the inn known as the George and Dragon which is bifurcated about two hundred yards along its course. The left-hand way leads through to Sonning and Wheelers Green; the right-hand way to Coleman's Moor Farm and Sandford Mill, then to Hurst and Twyford. So great an extension as the whole of Sonning may probably not at this stage be contemplated; but the development of the Erleigh Court and Holme Farm estates will have some effect on this. We will tentatively assume that Sonning is not in the picture, so at some point about Sandford Mill the river must be abandoned and an arbitrary boundary picked up. Now, aviation will in future play an increasingly important part in town planning and urban organisation, and with the increase of private flying different ideas in regard to distance and accessibility will arise, just as they arose when the railway and the internal combustion engine came to shape and dominate the life and livelihood of the community. One can therefore envisage municipal aerodromes on a large scale in or near any centre of importance. At Woodley there is the obvious site of the future town landing ground for the extended borough. We should, therefore, be disposed to take a fairly wide detour at this point, and still leaving the Loddon in its capricious and beautiful ways through Whistley, pick up a point on the Great Western Railway near Sonning Golf Course and follow the line to the present boundary of the town. AN ALTERNATIVE. It might be argued that this is undesirable since it leaves the Earley Mead and the new electrical transformer station, and even the site of the Reading Gas Company's new gas holder , in alien territory. If this be considered undiplomatic or inadvisable the alternative is to take the present boundary between Sonning and Earley and proceed to Earley Point on the Thames. One could then come down the centre of the river to the Kennet Mouth and join with the existing boundary at the Southern Railway bridge. There would be a distinct advantage in this arrangement since it is highly desirable that the historic Earley Mead shall remain a riverside pleasance for future Reading, and not suffer from the haphazard and unsightly development which marks the southern riverside between Caversham Bridge and Reading Bridge . The fact that Earley Mead is often flooded will be no deterrent to its use when the advice of modern engineers is sought. It may be assumed that as the extension of 1911 expressly excluded most of the Caversham Park estate and placed it in the parish of Eye and Dunsden, no attempt will be made to cross the Thames again in order to join up with the present borough boundary at Emmer Green. But two facts are pertinent here: one is that the municipal cemetery is at present outside the area of the local authority, and the other that building developments are rapidly proceeding along the Henley Road towards Play Hatch and in the vicinity of the new burial ground. Before 1887 the old Reading cemetery was outside the borough bounds. SIGNIFICANCE OF MAPLEDURHAM. In what is perhaps an unorthodox and inexpert manner was have sketched out the possible limitations of an ambitious Reading of the not very distant future. For the purpose of these notes any territorial adjustments on the north-west and west have been disregarded as relatively unimportant, although Purley and Mapledurham may eventually assume a significance which cannot be ignored. And now let us for a moment be Utopian and take for granted that the existing structure of society will not be so severely shaken that orderly and ethical advancement cannot continue along approximately existing lines.

We have picked up the Great Western Railway line near Sonning Golf Links and have followed it as an easy boundary to Reading. Suppose we do not take this course, but pass by an arbitrary way across the line, and include the whole of the village of Sonning, making the Thames our northern line of demarcation to the Kennet mouth. May not Reading then become a great city of the south and the centre of a new Diocese of Berkshire, with its stool and Cathedral Church at Sonning ? I fear that the answer will be that this is visionary; but such a vision would be but to restore to that Thames-side village some of those ancient ecclesiastical glories that go back into the dim recesses of time, possibly before the Danes came with fire and sword to lay waste the pleasant lands of Berkshire. And to those who fear that the move of industrialisation would play havoc with such a centre of historic charm and beauty, may we not say that there is a growing desire to see, and intelligent bodies to ensure, that vandalism shall be stayed and beauty conserved. We led off with a promise of some historic details of the areas included in our perambulation. It is to be feared that these must wait. But they shall follow. [Note: Mr. Dormer did indeed continue with his historical journey, in succeeding weeks.]

From the 'Reading Mercury', 28th October 1933: RAIL CAR LIKE AN AIRSHIP. To Run Between Reading and Slough. LUXURIES INSIDE. Britain’s first stream-line rail car will shortly be introduced by the Great Western Railway on its suburban services between Reading and Slough. It looks more like the giant gondola of an airship than a railway carriage, and it is the outcome of exhaustive tunnel tests to reduce wind resistance, which at speed requires considerable power to overcome. Each compartment is fitted with a clock and speedometer, and a microphone enables the driver to communicate with the guard or passengers. Flush fitting observation windows run along the top part and merge at each end into sloping control cabins. The interior is decorated in brown and green. The sides of the car are covered in mottled green rexine, and the roof in cream rexine. The floors are covered with insulboard to deaden noise, and green lino and mottled green carpets. All the woodwork is in walnut. Flush-fitting ceiling lights and lights on the under-side of the luggage racks are provided. The coach is heated by hot water heaters fed from the radiator. There is an emergency lever which stops the engine and applies the brakes when pulled down. The car is 62 ft. long and 11 ft. 4 ins. high. It weighs 20 tons, and has been designed for a maximum speed of 60 m.p.h. Seating capacity is for 69 passengers. The car is driven by a 130 h.p. heavy oil engine, using non-inflammable fuel, and this engine is almost identical to those fitted in some of the London ’buses. The sides of the car extend to within a foot of the track, so that practically the whole of the vehicle, including wheels, is enclosed in a stream-line case. Everything possible has been enclosed, even to the head and tail lamps, controlled from the driver’s seat, which are fitted flush with the case. The effect of this stream-lining has been to reduce wind resistance to one-fifth of that encountered by a similar square-ended car.

From the 'Reading Mercury', 18th

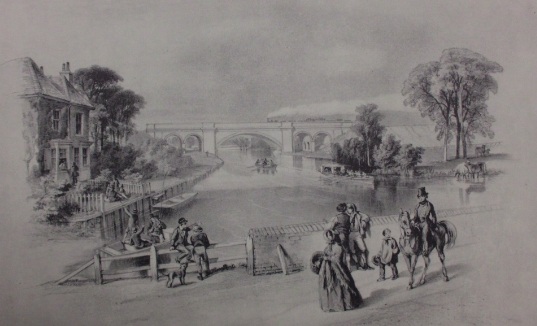

February 1933: THE KENNET'S MOUTH AT EARLEY. The Old Wharf and Ferry. BREACH FAMILY HISTORY. BY ERNEST W. DORMER. Among the local records which in recent years have been slowly emerging from dusty black tin boxes and similar dark repositories are some maps and deeds relating to the Liberty of Earley and its ancient manors. The present writer has, on more than one occasion, dealt with certain of these records in these columns, but there is still much of local historic interest which will well repay the salving. Among the subjects which have not before been touched upon are the ancient Wharf and Ferry, which were situated at the junction of the Thames and the Kennet where the mighty gas holder now looms like a dark colossus over the landscape. In endeavouring to deal with this area of land it must be remembered that the two embankments of the railways have almost entirely obliterated the original territorial layout; and care needs to be exercised where such a drastic reconstruction has taken place. It would be well, perhaps, to deal first with the Wharf . The Thames, in its course from Caversham Mill to Earley Point (about three-quarters of a mile this side of Sonning Lock) runs in an arc, and within this arc is the Kennet embouchure. The wide circular sweep can best be seen from the high embankment of the Great Western Railway. From very early times there existed in the Liberty of Earley six common fields and a common mead, the latter bordering the Thames from a spot just below the present Dreadnought Inn to Earley Point, where the boundary of the Liberty was situate. These great fields represented, until the enclosures of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the mainstay of economy in the district from long before the Norman invasion. The only one that concerns us in these notes is that called Wharf Field , which derived its name apparently from the presence of a wharf at the junction of the rivers. Wharf Field was the north-westerly of the six and reached to the angle formed by the Kennet and the Thames. On its western side it touched the boundary of the borough of Reading. The Wharf itself seems to have extended from a site now occupied by an inn called The Jolly Anglers on Kennet Side to the site of The Dreadnought. The actual point of confluence of the rivers was called the Mead Marsh ; it was subject to flood, and the Wharf therefore ran across in a north-easterly line rather than a triangular line between its two extremities. The origin of the Wharf has never been explained; in fact, few know that it ever existed at this spot, and no records have as yet been found to indicate its purpose or the produce, if any, that was landed there. It is referred to in 1669, upon an old map which is the writer's possession, simply as “The Wharf”, and to the south and east are depicted the numerous “shots” and acres of the Wharf Field. It is significant that upon this map there is indicated a lane running from the present London Road, opposite The Marquis of Granby , down to the Kennet, and called “The Lane leading to the Wharf”. CARRIAGE OF GOODS ON THE THAMES. It is sometimes forgotten that the carriage of goods on the river Thames is of very early origin. Quite apart from the bulk that could be carried in this way, there were no roads worth the name; the majority of ways were simply miry tracks impassable at certain seasons of the year, and the vehicles were unsuited for anything but personal transportation. Most of the merchandise went by pack-horse. The task of assembling on the spot the mass of material for the erection of such a building as Reading Abbey can thus be appreciated, for a considerable amount of the material was non-local. It is obvious, therefore, that carriage by water was greater than is popularly supposed. We have a record in this connection which is interesting. In the year 1205, King John, by letters patent, granted to William, the son of Andrew , “our servant”, the right to have one ship going and returning upon the Thames between London and Oxford, with his property and merchandise free and unmolested by any toll and exactions; and he was allowed freely and without hindrance to load that vessel wherever on the Thames he desired between these two cities. What hazards he encountered in his journeys must be left to the imagination; they were many if the state of the river in later centuries is any criterion. In 1350, Parliament passed its first Act against obstruction in the navigable highway of the river, and it may be that river-bound traffic continued henceforward to increase despite the wholesale disregard of the enactment by the fishermen, millers and riparian owners. But to return to the Wharf and its origin. Not the least significant fact about it is its early decay. One may assume that, although it is referred to in 1669 , the peak of its importance and usefulness had then passed, for contemporary documents have nothing to remark upon it. It is all very mysterious and may therefore be of very early origin. It will be remembered that about thirty-five years ago, when the Great Western Railway was widened, a Saxon cemetery was found near the Dreadnought on the piece of land called "Broken Brow" . The discovery raised some interesting problems, not the least intriguing of which was whether there had been an important settlement at Earley, altogether independent of Reading and Sonning, before the Norman invasion. The question has not yet been thoroughly explored, but it is interesting from the fact that the Wharf might conceivably have had its origin in such a settlement. At the moment it would not be safe to go further than this. ABBOT DEMANDS TOLL. There is one other suggestion which has been tendered as to its origin, but in the absence of documentary evidence it must be received with caution. The pre-1887 boundary between Reading and the parish of Sonning (which, of course, included the Liberty of Earley) was not, as one would suppose from the ease of such a natural landmark, the actual point of junction of the two rivers, but the aforesaid lane which terminated some three hundred yards from the river mouth. There are still remaining in Avon Place the fragments of an old chalk and flint wall which at one time formed the boundary line. The wall ran north and south, and turning east from it are still sections of an old cob wall which ran north-east across to The Dreadnought. This wall appears to mark the landward line of the Wharf. There was probably a good and sufficient reason, in remote times, for the original choice of boundary at this spot, but it is lost in the mist of time. It is notorious that ancient boundaries are sometimes inordinately perverse. Now, slightly to the west of the point at which the boundary strikes the Kennet was anciently a lock belonging to the Abbot of Reading and called Brokenbrow, or Brokenburgh lock. It is obviously associated with the piece of land upon which the Saxon cemetery was discovered, and the name would seem to be Saxon in origin. In the year 1404 the Abbot bethought him of an additional method of increasing the monastic revenues. Before traders could bring their merchandise by boat up to the common landing place at the High Bridge in Reading, or carry it thence, they were compelled to pay toll to the Abbot for passage through his lock and the waters which ran within the precincts of the Abbey. It is common knowledge that for several centuries the relations between the Gild Merchant of Reading and the Abbot were not exactly cordial, and the establishment of a wharf just outside the jurisdiction of the Abbot may have been the outcome of a determination of the merchants of Reading to evade the monasterial imposts and, after landing their produce at the Wharf at Earley, convey it overland without further interference. Similarly as a point of departure for London and Oxford bound traffic the Wharf would have been effectual in evading the abbatial exactions. This, then, may be an other reason for the origin of the Wharf; but, while it is entitled to consideration, undue weight must not be attached to it; there may have been other and more cogent reasons why the Wharf was fixed here, and they may yet come to light. GRANT FOR 99 YEARS. There is an old deed in existence which gives some further details of the neighbourhood in the early part of the 18th century. On May 29th, 1733, Richard Manley and Owen Haistwell, of Earley Court, granted to Peter Breach, of Sonning, fisherman, for 99 years a lease of a piece of ground, about four acres in extent, “heretofore a coppice of underwood upon the hanging of a hill towards Earleigh Wharfe and of a messuage built thereon, which ground was leased by Sir Edmund Fettiplace, Bart, to William Taplin, of Earley, yeoman, for the lives of John his son and John, son of Thomas Hill of Earley , reserving to the grantors all tithes”. The deed states that the messuage had lately been erected. The consideration money to be paid by Breach was 30s. a year and on his death a heriot of £3. Among the stipulations in the lease was one that there should be reserved to the grantors the “free liberty of Hawkeing, Hunting and Fowleing on the said premises at seasonable and convenient times” and the said Peter Breach, for himself, his executors and assigns covenanted that they would appear at each Court Baron “which shall be holden for the manor of Earleigh, otherwise Earley St. Bartholomew in the said County of Berks and doe and perform such suite and service as other the tenants of the said Manor of right ought to do and perform”. A word as to the parties in this transaction. Of Owen Haistwell, who may have held part interest in the manor, nothing appears to be known. Richard Manley was an attorney, a member of the Manleys of Cheshire, of long and influential ancestry. He became possessed of Erleigh Court by his marriage with the niece of Sir Owen Buckingham, who died in 1713. Richard Manley contested the seat for Reading in 1739, but was defeated by John Blagrave by three votes. He died in or about the year 1750. The Sir Edmund Fettiplace referred to was in possession of Erleigh Court prior to 1666, about which time it was purchased of him by Sir Owen Buckingham. Peter Breach was a member of an old Sonning family, and it is possible that the lease in 1733 marks their first territorial acquisition in Earley. There are records of them at Sonning as far back as the reign of Elizabeth, when we find that John Breach and William Breach were defendants in a Chancery suit where certain persons claimed, in 1585, divers lands in Sonning by descent in coparcenary. In 1721-22, Peter Breach, of Sonning Eye, husbandman, aged 60, deposed that his father occupied an estate of his own in Eye reputed worth about £40. In 1783, there was an Isaac Breach in occupation of the “bucks” standing below Earley Point, and in 1804 a Peter Breach was having trouble with the Thames Commissioners regarding an encroachment below Caversham Pound. Breach's Weir, which is referred to by John Taylor, the water poet, in the 17th century, was near the small islands at Earley Point, and for long it was a source of annoyance and danger to all who used the navigable part of the river. Despite repeated injunctions the Breaches clung tenaciously to their weir, but were at length forced to remove it. It should be noted that there are still descendants of the family resident in Reading. THE DREADNOUGHT'S PREVIOUS NAME. To revert to the lease to Peter Breach. It would now be difficult to locate the site of the buildings newly erected in 1733 on the land granted to him; but the old inn known as the Dreadnought deserves a word or two in this connection since it was the home of the Breach family for many years. A century or so ago it was called The Broken Brow – from that persistent place-name we have before encountered – and there is a tradition that long before it was an inn, it was a shooting box for the lord of the manor. The present building is about two hundred years old, and until early Victorian times appears to have been the home of the Breaches, who, in addition to being fishermen, owned reed or withy beds on various parts of the river. Old inhabitants of Earley, notably Mr. George B. Wheeler , dairyman, of Kennet's Mouth, who has spent his whole life in the district with which these notes are concerned, can recall that The Dreadnought at one time had a skittle alley, but it was burnt out by accident many years ago. There used to be some fine walnut trees on the green beside the inn. It may be possible to learn when, and why, the old inn changed its name to The Dreadnought, a very much less interesting and euphonious sign. It must have been before 1868. And now a few words as to the Ferry. It is probably not of such ancient usage as the Wharf, but in the thirteenth century it was within easy distance of historic establishments. Facing it on the rising ground of the Chilterns was the castellated home of William Mareschal, Earl of Pembroke, that “very perfect knight” who was Regent of England during the boyhood of Henry III, and who lies buried in the Temple church, London; to the south-west loomed the flint and stone mass of Reading Abbey; to the east the manor place of the Bishops of Sarum at Sonning; and to the south-east, in a belt of forest trees, the more modest steading of the knightly family of the de Erleghs . And yet we hear nothing of this river crossing until quite recent times. A ferry-boat was first provided in 1810, and the ubiquitous Peter Breach, a descendant of the Peter of the coppice, was appointed ferryman at wages of 20s. a month. He was then probably living at The Broken Brow. He was authorised and empowered to collect a toll of 2d. per horse. At the end of 1812 a James White took over the duty at 15s. a week, but this increase of emoluments appears to have been coupled with additional duties as keeper of Blake's Lock on the Kennet, the legitimate successor of the Abbot's lock . In 1823 we learn that the Ferry was operated by a chain. Lying a few yards back from the river is still the small “ferryman's cottage”, which was built in 1843 in place of a former cottage that had become ruinous. Many middle-aged folk can remember the ferry and the pleasant scene of the towing horses being ferried across the river, for it was not until 1892 that the present towpath bridge was built and the Great Western Railway bought up the ferry-house and other property at Kennet's Mouth which had belonged to the Conservancy. Before leaving the Ferry there is one item of interest that may claim a moment's notice. From very early times a bridle path led across the Earley meadows to Sonning. It still does. It commenced at a spot of late years occupied by East's boathouse , and crossed the two railway embankments. Some years ago the entry to the path was diverted to a spot between the two embankments, and only one – the Great Western – had to be crossed. Within the last few years it has been diverted again and now commences actually to the north of the Great Western Railway line and takes a rather undignified course along the northern face of the embankment and by an almost right-angled turn reaches the towpath. One wonders how, in times of high flood, it is possible to reach the entry of the path at the river mouth. In part this ancient route must have been in close contiguity to the Wharf, and served a very useful purpose in mediaeval days before the present London road from Reading to Sonning had been made.

|

||||||

|

Any Feedback or comments on this website? Please e-mail the webmaster |